by John Pickard

This week sees the centenary of the death of Lenin. His significance to the socialist movement is apparent from the fact that the date has even been marked in the more serious capitalist press, although always to demonise him and to misrepresent the ideas for which he stood. (See here, here, here and here)

It is important that the socialist movement pays due credit to Lenin on its own terms, rather than those of our enemies. Among the founders, theoreticians and important fighters in our traditions, there are particular giants, whose contributions far exceeds that of most. Alongside Marx, Engels, and Trotsky, Lenin was one of those.

Lenin added considerably to the great arsenal of Marxist theory, and he played the central role in the Russian October 1917 Revolution, the first time in history that the working class had successfully taken and held power in any country in the world. In one short article it is not possible to give full credit to the importance of Lenin’s life and works and we would encourage all Left Horizons readers to go back to his works and to study and discuss them at first hand. The full Lenin archive can be found here.

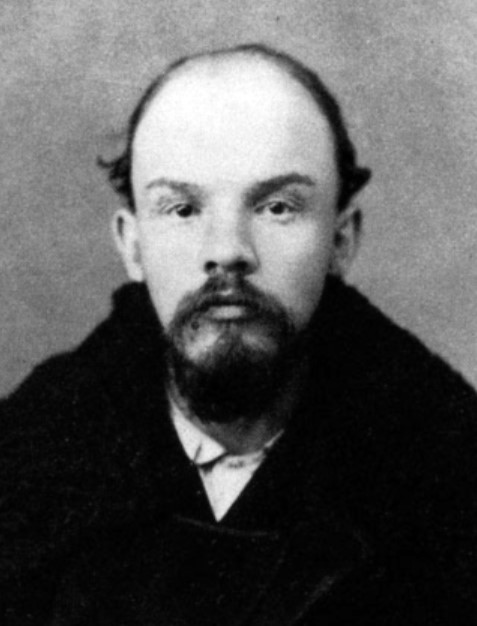

Lenin’s early political activity, in the Tsarist Empire, would have been unfamiliar to us, and extremely difficult in comparison to conditions that we face in the UK or in the West in general today. Russia was a ‘prison house of nationalities’ in the sense that Great Russian chauvinism dominated all other peoples within the Empire. But it was also a ‘prison house’ in a literal sense, where activity in the socialist movement risked jail and exile. Early on in his life, the young Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, an active socialist even in his student youth, experienced both a term in jail and exile in Siberia.

Lenin studied the work of Marxists in great depth

In his youth, in prison and then in exile, Lenin (his nom de guerre from around the age of 30 onwards) had time to study the works of Marx and Engels assiduously, as well as the writing of other important theoreticians of the European socialist movement of that time, like Plekhanov, a fellow Russian, and Kautsky, the Czech-Austrian theoretician. From very early on, Lenin was able to make important contributions on the development of capitalism in the Russian Empire.

After his exile, Lenin renewed his activity as a socialist, but was persuaded that his contribution to the movement was too important to risk being arrested again. So with his wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya, who he met as a fellow activist, he moved overseas, first to Berlin, the first of many places of exile, and later in Paris, London and Switzerland.

Lenin’s important early years as a Marxist were shaped by two fundamental ideas. The first was that the ‘social democrats’ (as socialists called themselves at the time) should base themselves on the working class, even though it was a minority of the Russian population.

They wanted to distinguish themselves from the intellectuals and middle-class radicals who, on the one hand flirted with terrorism and assassinations, and on the other hand, looked to the peasantry – the big majority of the population of the Russian Empire – as the motive force for revolution. Indeed, the execution, in 1887, of his elder brother for his part in the attempted assassination of the Tsar, had a profound effect on Vladimir. Although the industrial working class was a minority in the population, it had a growing social weight by virtue of its concentration in relatively few but very large and modern factories.

A newspaper as a focus of party organisation

The other central idea, expressed in his early book What is to be done? (1902), was the need for the social-democratic party to counteract the baleful effect of the Okhrana, the secret police, by moving away from ‘amateurishness’ within the party membership, and developing a more professional and tightly organised structure. Lenin saw the production of a socialist newspaper, the first of its kind being Iskra (‘Spark’), as an essential means of political education, agitation and organisation. The very process of clandestine distribution of such a newspaper – smuggled into Russia from abroad, circulated and then read out and discussed in workers’ groups – would reinforce the organisation of the social democratic movement, as well, of course, as providing political education and leadership.

Later distortions of his ideas by Stalin, had Lenin favouring ‘iron discipline’ in the party, but that was never the reality in practice, either in the early Bolshevik years, or even later, after the Communist Party ‘officially’ banned factions in March 1921.

Lenin was at great pains to promote what he saw as a correct approach to all important issues – seeking clarity where there was vagueness and urging determination instead of indecision – but he did not oppose in principle or in practice the right of other social democrats to disagree with him. That is evidenced in the fact that so much of his writing was polemical, where he used the mistakes of his political opponents, not to discipline them or hound them out of the party, but to educate the rank-and-file membership.

There were always different strands of opinion in the social-democratic movement and even after the social-democratic party split into two factions in 1903, between a minority (Mensheviks) behind Martov, and a majority (Bolsheviks) behind Lenin, there were currents – Trotsky’s being one of them – that were aligned to both or neither.

The Right of Nations to Self-Determination

One area of Lenin’s writings that is worth noting (among many, it has to be said), is his policy on the National Question, expressed in the book The Right of Nations to Self-Determination. Much of this was a polemic against Rosa Luxemburg, another great figure of the labour movement of that time, who was of Polish extraction, but who was active in the German labour movement. This was a key issue for the Russian labour movement, because the Tsarist Empire was a huge mixture of many different nationalities.

Lenin argued for internationalism and the greatest-possible unity of workers of all nationalities, but he also made it clear that the unity of workers had to be voluntary or it would not succeed. Likewise, the unification of states and nations had to be voluntary, even to the extent, he argued, that smaller nations had the right, if they so wished, for self-determination.

Lenin’s firm internationalism was demonstrated in the outbreak of the First World War, when all of the parties of the Second Socialist International supported their ‘own’ ruling class in the conflict. The scale of the betrayal by the different leaders of social democracy is difficult for us to comprehend more than a century later, but it represented a monumental (and unexpected) collapse of a once mighty international movement, which had millions of members across Europe and the world. Lenin’s first thoughts on reading that the German Social Democrats had voted to support the German government’s war credits was that the story was a fake.

Lenin became one of a tiny minority of leaders – enough “to fill two stage-coaches” – who continued to support an internationalist position. Lenin explained the imperialist character of the war, from the point of view of both of the two warring alliances, the Anglo-French-Russian (Triple) Alliance, and the German-Austro-Hungarian Alliance. Rather than fight one another, he argued, the task for workers was to fight their own ruling class as the ‘main’ enemy.

Lenin’s perspective was that revolutions would develop at some point within the belligerent states, and in this he was right, although even he didn’t foresee with what speed revolutions would break out. He gave a lecture to Swiss students (on the 1905 Russian revolution) in January 1917. “We of the older generation”, he said, “may not live to see the decisive battles of this coming revolution.” Weeks later, Russia was engulfed in revolutionary upheaval.

February Revolution threw up ‘soviets’ for a second time

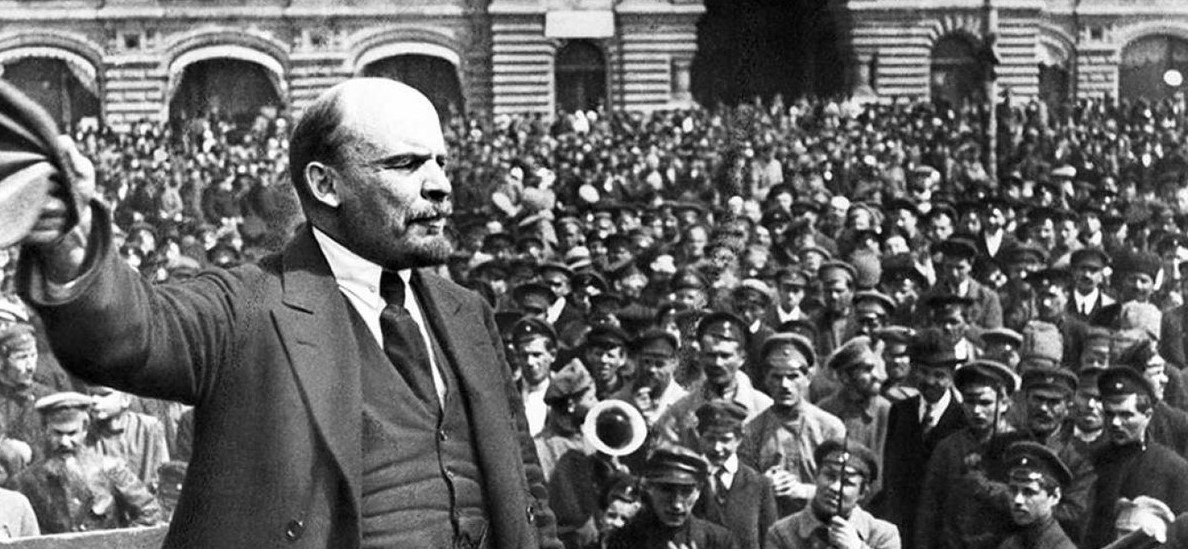

It is probably in relation to his leadership of the Bolsheviks in 1917 that Lenin is most widely known. When the February revolution broke out, he understood immediately that the only force that could defend the revolution against reaction was the working class. Not only that, but this policy inevitably meant the further extension of the revolution.

Unlike some Bolshevik leaders who were vacillating, he argue for “no support” for the capitalist ministers installed in the post-February government. It was necessary for Lenin to wage a fierce political polemic, not only against the Menshevik tendencies in the workers’ movement, those who would seek to compromise with capitalist interests, but even against the vacillators in his own party. His April Theses and Letters from Afar and other works from that period outlined the course he believe the Bolsheviks should take, demanding ‘Bread, Peace and Freedom’, later amended to ‘Bread, Peace and Land’.

Lenin’s outlook coincided at this point exactly with that of Trotsky and it marked the beginning of a close collaboration between the two that would last the rest of Lenin’s lifetime. Once Trotsky and his followers formally joined the Bolshevik Party, in July 1917, Lenin would say, “there is no better Bolshevik”.

Lenin based his policy on the experience of the earlier 1905 revolution, when workers throughout Russia had set up revolutionary councils – ‘soviets’ – an experience that was repeated on an even greater scale in February 1917. Not only were there workers’ soviets in the main cities – Petrograd being the most important – but mutinous soldiers and impoverished peasants in the villages also set them up.

The soviets for Lenin and Trotsky were not only organs of struggle. They were an embryo of a workers’ and peasants’ government and the slogan that gave real meaning and substance to the revolution in October 1917, was “All power to the soviets”.

Among the many writings of Lenin, it is worth discussing in depth State and Revolution, a book written around this time, in which Lenin developed his arguments about the role of the soviets. Based on the writings of Marx and Engels, and the experience of the Paris Commune of 1871, Lenin explained the huge significance of the soviets as a form of government, in which “every cook can be a prime minister”.

Perspective and programme of Lenin and Trotsky was international

It was after the assumption of power by the All-Russian Congress of Soviets that an executive of ministers (‘people’s commissars’) was elected to manage the first ever workers’ state in history, an executive committee that included Trotsky and, as its chair, Lenin.

It is important to note that the perspective of Lenin and Trotsky was not to ‘build socialism’ in what was the most industrially-backward country of Europe. But they believed that the only course that would maintain the gains of the February revolution was the assumption of power by the soviets and, even more importantly, that a workers’ revolution in Russia would be a prelude to revolutions elsewhere in Europe.

‘Socialism in One Country’ was a later (1924) Stalinist distortion of Lenin, a political ‘theory’ to justify the existence and permanence of the growing bureaucracy of the time. Rather than having the young soviet republic isolated, as it were, by the mistakes of revolutionaries elsewhere, the isolation became the default strategy of the Stalinists, and Comintern policy was based on maintaining Russia as the only workers state. In in a later period, the Stalinists consciously betrayed revolutions abroad.

Many of the ideas that carried the October Revolution, like Lenin’s ideas in general, have been distorted much over the years. One of the best descriptions of the internationalist programme and perspective of Lenin at that time is Lenin and Trotsky: What they really stood for.

Although the perspective of European revolution was correct – a whole number of revolutionary events took place in the West, most notably in Germany and Hungary – for a variety of reasons, the Russian revolution remained isolated for whole historical period. That meant that the young Russian workers’ republic was beset from the beginning by enormous, and one could say almost insurmountable, obstacles.

Working class and Communist Party decimated by Civil War

First there was the Civil War, during which the young workers’ government was desperately defending its very existence against the capitalists’ armies of intervention and White armies. But following that, with the cream of the Communist Party (as it had now become) killed in that war, with the working class reduced in size, with industrial production crippled, and with many regions facing famine, the Russian workers’ state faced looming disaster.

As it waited for a successful revolution in the West, when much more highly-industrialised socialist states could come to their aid, therefore, the Russian workers’ state was forced to make concessions to some limited capitalist development. This was the New Economic Policy, a programme that increased food production and kick-started industry, but at the cost of enriching a layer of well-to-do peasants and middlemen, but alongside them, a layer of bureaucrats in both the Party and the government. With the working class so decimated, many former Tsarist officials were brought into running the state, fitting in well with the new ‘communist’ bureaucracy.

It is easy for us to say, with the benefit of a century of hindsight, but it is arguable that both Lenin and Trotsky may have underestimated both the extent and the depth of the bureaucratic degeneration that was already taking place , particularly around the figure of Stalin. Stalin, as Trotsky ably explained in his biography of him, was a secondary, uncharismatic, figure and one hardly known by party activists before 1917 – and probably even for some time afterwards. But he was seen as an ‘organiser’, someone who ‘got things done’ and after he was put into a number key positions in the party from 1917 onwards (and with Lenin’s initial support) he was able to establish a network of personal support, based entirely on his patronage, among like-minded nonentities.

Lenin was becoming aware of the growing bureaucracy within the party and the state. By the time of his first stroke, in May 1922, there was already tension between him and Stalin, and this increased, not only on the question of bureaucracy in the Party, but also on the National Question. Before his death, Lenin was planning, with Trotsky, a broadside against Stalin and his acolytes over Great Russian chauvinism in their treatment of the communist movement in Georgia. Stalin had also managed to insult Krupskaya, so much so that she refused to have any more dealings with him.

Lenin largely incapacitated for nineteen months

Unfortunately, after that first stroke, Lenin was more or less incapacitated for the rest of his life and was unable to conduct a struggle with Stalin or to influence – and correct – the mistakes of the Communist International. After his death, the machinations against Trotsky, Lenin’s ‘natural’ successor, began in earnest. Lenin’s last testament, in which he called explicitly for Stalin’s removal as general secretary, was suppressed by Stalin. That testament circulated in a clandestine manner – Trotsky also refers to it – until it was ‘officially’ revealed by the Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, in 1956.

At the time of Lenin’s death, Trotsky had been in Southern Russia for health reasons, and some of the other Communist leaders managed to manoeuvre, by means of incorrect messages about the arrangements, for Trotsky to miss Lenin’s funeral. And so the one-sided civil war of the Stalinist bureaucracy against all the ‘old Bolsheviks’ picked up pace.

The Stalinists embalmed Lenin’s body, against his wishes and those of his widow. His body rests to this day in the Lenin mausoleum in Moscow. But as with his body, Lenin’s ideas were embalmed and emptied of all revolutionary content.

While the Soviet state, right up to its collapse in 1989, published tons of editions of Lenin’s works, in every language, workers would be arrested and exiled, or worse, for having the temerity to refer to them in public or discuss them in private. Pictures and busts of Lenin were everywhere and, until it was changedback under Yeltsin, Petrograd had been named Leningrad. But the real ideas and tradition of Lenin were nowhere.

The works of Lenin are worthy of reading and re-reading. They should be analysed in Marxist discussion groups today. Unlike the Stalinists, we will not turn Lenin into an icon or a saint. Like all of the great socialist leaders he made mistakes and we have to look at his writings in a critical way, to see what applies today and what may not, or what may have changed in the hundred years since he wrote.

But nonetheless, Lenin’s life and works are essential elements in any Marxist theoretical education. We have to pay due tribute to a giant of socialist thought and action. Go and read his books.

A well thought through article on Lenin showing a measured appreciation of this great Marxist. Quite different to the overlaudertory stuff produced by the IMT

Thank you for writing such a clear, simple and understandable article on Lenin. The mists of history have become a little clearer for me.