Andy Ford, Warrington South CLP

At 3 am on 22nd June 1941 three million German troops launched their attack on the Soviet Union, supported by 300,000 Finnish troops and two Romanian armies totalling 350,000 men. It was the biggest attack in the history of warfare and the struggle on the Eastern Front in reality determined the outcome of the Second World War.

Operation Barbarossa, as it was called by Hitler, eventually sealed his doom but only at a truly horrific cost. Twenty million Russian civilians died, five million Soviet troops were captured, of whom three million perished of disease, starvation and maltreatment, and at least 500,000 Jews and Romani were shot by Nazi death squads in 1941. It was on the basis of having a planned economy that the Soviet Union eventually triumphed, but at a tremendous price and it was despite the misjudgements and crimes of Stalin.

The Red Army before the war

After the 1917 Russian Revolution, Trotsky had organised the Red Army virtually from scratch and it became a formidable fighting force able to defeat the forces of the counter-revolution and the 21 armies of intervention sent by surrounding imperialist countries against the revolution. In the course of that struggle a new generation of talented commanders were thrown up – like Yakir who led the Red Army military academy, Tukhachevsky, who developed the idea of tank and air support as a means of modern warfare, and Frunze, who had defeated Kolchak in Siberia. Together the three came up with the Russian military doctrine of ‘deep operations’ or ‘deep battle’ which is recognised to this day as a key innovation in military thinking.

Deep operations played to the strengths of the Soviet Union where its vast territory and manpower allowed for defence in depth, to first exhaust an enemy attack, and then spring back to encircle and destroy an invader. The idea anticipated the likelihood that any invaders of the USSR would be mobile and equipped with more mechanised weaponry. Where ’deep operations’ were deployed properly, like at Stalingrad, or in Operation Bagration in 1944, it led to the greatest Soviet victories of World War Two.

However, Stalin did not tolerate anyone whose talent was exceptional, because he saw them as potential competitors to himself. Frunze died in 1925, likely as the result of a deliberately botched operation, and both Yakir and Tukhachevsky were arrested, tortured and murdered in the purges of 1937. In fact, huge numbers of the officer corps of the Red Army were arrested in 1937, right down to company and battalion commanders, because Stalin feared that the army could remove him from power, and, such was his unpopularity, he feared that it was a likely development.

By purging the cream of the leading cadres of the Red Army, Stalin drastically weakened the defences of the Soviet Union. So just as the Nazi threat was growing, the Red Army was a shadow of its former self. The Winter War of 1939-40 against little Finland cruelly exposed its deficiencies. Hitler’s confident prediction, that “if we kick in the door the whole rotten edifice will collapse” wasn’t far from the truth. Having debilitated his own armed forces, Stalin at first attempted to keep the Nazis at bay through a diplomatic deal.

The Hitler-Stalin Pact

Given the that it was the historic goal of the Nazis to destroy the ‘Bolsheviks’, the world was stunned in August 1939 when the news came through that Stalin had signed a treaty with Nazi Germany – although it was an outcome Trotsky had predicted as early as 1934. The two countries pledged mutual neutrality and the Soviet Union was committed to supply raw materials to the Nazis in return for machinery, locomotives, military supplies and advanced manufactures.

In the following two years, Stalin supplied the Nazi war machine with a million tons of grain, 900,000 tons of oil, 100,000 tons of cotton and half a million tons of phosphate fertiliser. In Germany, goods were in short supply because of the British naval blockade. In addition, the pact provided for the division of Poland and the Soviet occupation of the Baltic states.

When the Hitler-Stalin Pact came into being, so-called ‘Communist’ Parties all over the world, similarly degenerated along Stalinist lines, had to turn 180 degrees. From having been denouncing “fascist aggression” and demanding a united front against Hitler, they suddenly switched – sometimes, it was joked, even in mid-speech – to denouncing the war as a “conflict between imperialists” where neither side could be supported.

Stalin’s motives in the pact were two-fold. He used it to divert Hitler to the west; but he also knew that the Red Army at that time was a broken reed after his purges. But Stain went far further than he had to do to deflect the Nazi threat. This was no arms-length diplomatic deal, borne out of dire necessity; it was an agreement enthusiastically supported and put into effect by the Stalinist bureaucracy.

Russian bureaucrats toasted ‘The Fuhrer’

In Moscow, the exiled leaders of the Polish Communist Party were shot. Molotov, the Soviet Foreign Minister, sent a telegram to the Germans to congratulate them on having occupied Warsaw and at banquets of the Russian bureaucracy, toasts were drunk to ’the Fuhrer’. German anti-fascists were sent to the Gestapo and the Soviet Foreign Ministry was purged of Jews.

Worse was to come, however. Instead of using the time bought by this repellent pact to build up the defences and the readiness of the Red Army, Stalin attempted to ingratiate himself with Hitler. Military fortifications on the western border of the USSR were destroyed in 1940. Later, when information came from Soviet intelligence, German deserters, or the ‘Red Orchestra’ in Japan and even from Winston Churchill that a Nazi invasion was imminent, Stalin dismissed it all as ‘forgeries’ and ‘provocations’.

The build-up of nearly four million German and allied troops on the western border of the Soviet Union was ignored. When a German soldier swam across the River Bug the night before the invasion, to warn the Soviets, he was also ignored, and on some accounts, shot.

The invasion: Operation Barbarossa

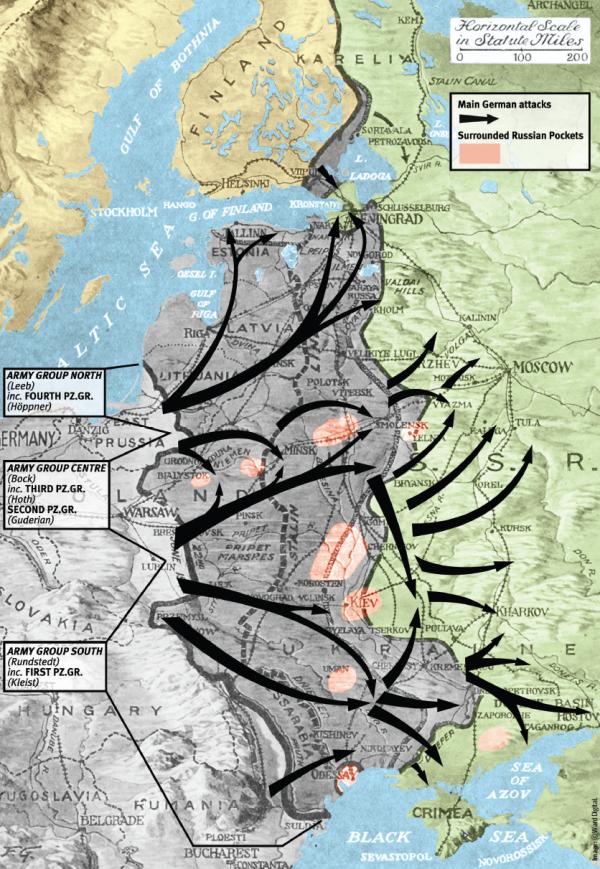

Hitler had instructed his armies to seize three key objectives: Leningrad, Moscow and the Donbas industrial region, also important for coal and oil. That meant seizing the key Soviet political centres and lines of communication, and probably two thirds of Soviet industry.

The Nazis anticipated a swift knockout-blow and the seizure of Moscow within six months, by the winter 1941. The German forces were organised into Army Groups North, Centre and South around these three objectives. The plan was for the main army to drive at speed into Russia and for the rear areas to be pacified by the notorious Einsatzgruppen or death squads, made up of the dregs of society and commanded by Nazi zealots.

Captured urban centres deliberately starved by Nazis

These squads were given the task of hunting down Jews and terrorising the civilian population into compliance. A special order, the ‘Commissar Order’ stated that anyone in a political leadership role had to be shot on capture, and the war was explicitly characterised as one of racial extermination with the “most brutal violence to be used”. Hitler outright ordered that the urban centres were to suffer starvation, once they were occupied, to free up space for his fantasy German Empire.

So, at 3 am on June 22nd the Luftwaffe took off to bomb the Soviet airfields. Thanks to Stalin’s criminal laxity, 1,200 planes, one third of the Red Air Force, was destroyed on the ground. German tank formations penetrated deep into Belarus, while Romanian and German forces attacked Ukraine. Despite this, for the first crucial hours, Stalin forbade the Red Army to even fire back and the results were plain to see.

The Baltic States went over to the Germans virtually without a fight and German tanks encroached 80 miles into Soviet territory in the first 24 hours. The city of Minsk fell within two weeks, with 324,000 Red Army troops taken prisoner and, through a succession of disastrous encirclements, the Soviets lost close to a million men. At Smolensk half a million Russians were killed or taken prisoner, at Kiev in the Ukraine, another half million were lost and by September, Leningrad was cut off.

The Red Army had been left without leaders because of the insane purges of 1937 and many Russian soldiers had no intention of dying for Stalin and so they surrendered in droves. They were not to know that German captivity was far worse – three million Soviet prisoners died in German hands.

Resistance of the Brest Fortress

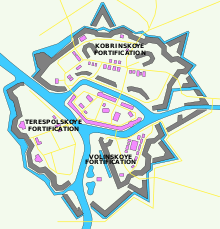

Only at the Brest Fortress, on the western border of the USSR, did the Red Army show what it was capable of. When the attack came it was the weekend and many officers were in the town, and in the fortress itself many soldiers had their wives and children visiting. Despite this, the Red Army made the most incredible defence against a five-to-one superiority.

Those who could returned to the fortress where they found terrified soldiers and civilians hiding from the bombardment in the bomb-proof cellars. However, they proceeded to mount a defence with whatever they had to hand. The Germans attacked repeatedly, but were driven back time after time in close-quarters fighting and they had to take the approach of levelling each building one after the other. Even then, resistance continued from the cellars, from both the soldiers but also their wives.

Short of water and food, the majority of the women and children surrendered six days after the invasion, but it took the Germans until the end of July to secure the fortress. After the war, an inscription was found scratched into one of the cellar walls “We will die but never leave the fortress 20.7.41” and a German military magazine showed flamethrowers in use at Brest in August 1941.

Brest resistance delayed advance on Moscow

One strange fact about the stubborn Brest defence is that the Soviet high command did not even know it had happened until nine months later, when they captured the papers of the German 45th Infantry Division near Orel. The defenders of Brest had lost all radio contact in the first days of the defence, and no-one had escaped death or imprisonment. Of those Russian officers commanding at Brest, Commissar Fomin was wounded and shot on capture, Captain Zubachov died in German captivity, and Major Gavrilov was severely wounded, captured, and miraculously survived four years as a prisoner of war before retiring to the Kuban after the war.

But it may be that the time it took to end the resistance at Brest had delayed the advance on Moscow sufficiently for the Germans to then be thwarted by the Russian winter. Brest was certainly a warning to the Nazis of the fighting qualities of the Red Army, and that battle prefigured the epic battle at Stalingrad the following year where the Red Army broke the back of the Wehrmacht on the Eastern Front.

Stalin’s cowardice and ineptitude and the masses courage and heroism

The Brest defence was a stark contrast to the personal cowardice of Stalin himself, who never visited the front line in the whole of the war. In fact, he was quoted (by Khrushchev) as saying a week after Operation Barbarossa, that “…great Lenin built this country and we shitters have fucked it up” before running away to hide in his country dacha. When the Politburo members came to see him – because he had not answered the phone for three days – he fully expected to be arrested for his crimes. Instead, the nodding dogs of the Politburo begged him to take charge again! And so, hesitantly, with mistake after mistake, the Soviet Union began to get organised to repel the Nazi hordes.

Despite the enormous impact of the Operation Barbarossa, devastating a large area of the Soviet Union, killing or capturing millions of soldiers, conquering a large part of the industrial heartlands of Russia, its ultimate goal was to fail. Notwithstanding the waste and bureaucracy, the advantages of a state-owned and planned economy were worth dozens of armies for the Soviet Union.

Factories removed to the safety of the East

Russia was able to withdraw entire factories, lock, stock and barrel, hundreds of miles to the safety of the East. Russia was able to draw on the vast reserves of its population and the raw materials that were well out of reach of the Nazis. Arms production to the West of the Urals increased immeasurably, until by the end of the war Russia was able to hurl tens of thousands of tanks and aircraft into the war. As it had been in the first years of the Red Army after the Revolution, a new, younger generation of commanders rose to the task and were able to drag the Red Army back to full fighting fitness.

The Second World War, despite the impression given in Hollywood films, was predominantly fought out on the Eastern Front after Operation Barbarossa. In terms of the deployment of the German Army, the war against Russia occupied by far the greatest bulk of its resources. The untold number of casualties on the Eastern Front on both sides, civilians as well as combatants, adding up to tens of millions, completely eclipses the war in the rest of Europe. Eighty years on from the beginning of that conflict, the scars and memories of that war in Eastern Europe still run deep and are woven into the political and social fabric of society.