By Michael Roberts

I’m sure when this disaster is over, mainstream economics and the authorities will claim that it was an exogenous crisis nothing to do with any inherent flaws in the capitalist mode of production and the social structure of society. It was the virus that did it. This was the argument of the mainstream after the Great Recession of 2008-9 and it will be repeated in 2020.

As I write the coronavirus pandemic (as it is now officially defined) has still not reached a peak. Apparently starting in China (although there is some evidence that it may have started in other places too), it has now spread across the globe. The number of infections is now larger outside China than inside. China’s cases have trickled to a halt; elsewhere there is still an exponential increase.

This biological crisis has created panic in financial markets. Stock markets have plunged as much 30% in the space of weeks. The fantasy world of every rising financial assets funded by ever lower borrowing costs is over.

Even before Covid-19, capitalist economies were slowing

COVID-19 appears to be an ‘unknown unknown’, like the ‘black swan’-type global financial crash that triggered the Great Recession over ten years ago. But COVID-19, just like that financial crash, is not really a bolt out of the blue – a so-called ‘shock’ to an otherwise harmoniously growing capitalist economy. Even before the pandemic struck, in most major capitalist economies, whether in the so-called developed world or in the ‘developing’ economies of the ‘Global South’, economic activity was slowing to a stop, with some economies already contracting in national output and investment, and many others on the brink.

COVID-19 was the tipping point. One analogy is to imagine a sand-pile building up to a peak; then grains of sand start to slip off; and then comes a certain point with one more sand particle added, the whole sand-pile falls over. If you are a post-Keynesian you might prefer calling this a ‘Minsky moment’, after Hyman Minsky, who argued that capitalism appears to be stable until it isn’t, because stability breeds instability. A Marxist would say, yes there is instability but that instability turns into an avalanche periodically because of the underlying contradictions in the capitalist mode of production for profit.

Not an ‘unknown unknown’

Also, in another way, COVID-19 was not an ‘unknown unknown’. In early 2018, during a meeting at the World Health Organization in Geneva, a group of experts (the R&D Blueprint) coined the term “Disease X”: They predicted that the next pandemic would be caused by an unknown, novel pathogen that hadn’t yet entered the human population. Disease X would likely result from a virus originating in animals and would emerge somewhere on the planet where economic development drives people and wildlife together.

Disease X would probably be confused with other diseases early in the outbreak and would spread quickly and silently; exploiting networks of human travel and trade, it would reach multiple countries and thwart containment. Disease X would have a mortality rate higher than a seasonal flu but would spread as easily as the flu. It would shake financial markets even before it achieved pandemic status. In a nutshell, Covid-19 is Disease X.

Viruses linked to wild-life

As socialist biologist, Rob Wallace, has argued, plagues are not only part of our culture; they are caused by it. The Black Death spread into Europe in the mid-14th century with the growth of trade along the Silk Road. New strains of influenza have emerged from livestock farming. Ebola, SARS, MERS and now Covid-19 has been linked to wildlife. Pandemics usually begin as viruses in animals that jump to people when we make contact with them. These spill-overs are increasing exponentially as our ecological footprint brings us closer to wildlife in remote areas and the wildlife trade brings these animals into urban centres. Unprecedented road-building, deforestation, land clearing and agricultural development, as well as globalized travel and trade, make us supremely susceptible to pathogens like corona viruses.

There is a silly argument among mainstream economists about whether the economic impact of COVID-19 is a ‘supply shock’ or a ‘demand shock’. The neoclassical school says it is a shock to supply because it stops production; the Keynesians want to argue it is really a shock to demand because people and businesses won’t spend on travel, services etc.

But first, as argued above, it is not really a ‘shock’ at all, but the inevitable outcome of capital’s drive for profit in agriculture and nature and from the already weak state of capitalist production in 2020.

Production, trade and investment

And second, it starts with supply, not demand as the Keynesians want to claim. As Marx said: “Every child knows a nation which ceased to work, I will not say for a year, but even for a few weeks, would perish.” (K Marx to Kugelmann, London, July 11, 1868). It is production, trade and investment that is first stopped when shops, schools, businesses are locked down in order to contain the pandemic. Of course, then if people cannot work and businesses cannot sell, then incomes drop and spending collapses and that produces a ‘demand shock’. Indeed, it is the way with all capitalist crises: they start with a contraction of supply and end up with a fall in consumption – not vice versa.

Some optimists in the financial world are arguing that the COVID-19 shock to stock markets will end up like 19 October 1987. On that Black Monday the stock market plunged very quickly, even more than now, but within months it was back up and went on up. Current US Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin is sure that the financial panic will end up like 1987. “You know, I look back at people who bought stocks after the crash in 1987, people who bought stocks after the financial crisis,” he continued. “For long-term investors, this will be a great investment opportunity.” “This is a short-term issue. It may be a couple of months, but we’re going to get through this, and the economy will be stronger than ever,” the Treasury secretary said.

Faltering stock-market

Mnuchin’s remarks were echoed by White House economic adviser Larry Kudlow, who urged investors to capitalize on the faltering stock market amid coronavirus fears. “Long-term investors should think seriously about buying these dips,” describing the state of the U.S. economy as “sound.” Kudlow really repeated what he said just two weeks before the September 2008 global financial crash: “for those of us who prefer to look ahead, through the windshield, the outlook for stocks is getting better and better.”

The 1987 crash was blamed on heightened hostilities in the Persian Gulf leading to a hike in oil prices, fear of higher interest rates, a five-year bull market without a significant correction, and the introduction of computerized trading. As the economy was fundamentally ‘healthy’ so it did not last. Indeed, the profitability of capital in the major economies was rising and did not peak until the late 1990s (although there was a slump in 1991). So 1987 was what Marx called a pure ‘financial crash’, due to the instability inherent in speculative capital markets.

But that is not the case in 2020. This time the collapse in the stock market will be followed by an economic recession as in 2008. That’s because, as I have argued in previous posts, now the profitability of capital is low and global profits are static at best, even before COVID-19 erupted. Global trade and investment have been falling, not rising. Oil prices have collapsed, not risen. And the economic impact of COVID-19 is found first in the supply chain, not in unstable financial markets.

Health diagrams going the rounds

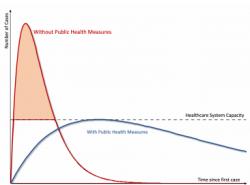

What will be the magnitude of the slump to come? There is an excellent paper by Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas that models the likely impact. He shows the usual pandemic health diagram doing the rounds. Without any action, the pandemic takes the form of a curve, leading to a huge number of cases and deaths. With action on lockdowns and social isolation, the peak of the curve can be delayed and moderated, even if the pandemic gets spun out for longer. This supposedly reduces the pace of the infection and the number of deaths.

Public health policy should aim to “flatten the curve” by imposing drastic social distancing measures and promoting health practices to reduce the transmission rate. Currently Italy is following the Chinese approach of total lockdown, even if it may be closing the stable doors after the virus has bolted. The UK is attempting a very risky approach of self-isolation for the vulnerable and allowing the young and healthy to get infected in order to build up so-called ‘herd immunity’ and avoid the health system being overwhelmed. What this approach means is basically writing off the old and vulnerable because they are going to die anyway if infected and avoiding a total lockdown that would damage the economy (and profits). The US approach is basically to do nothing at all: no mass testing, no self-isolation, no closure of public events; just wait until people get ill and then deal with the severe cases.

Malthusian answer

We could call this latter approach the Malthusian answer. The most reactionary of the classical economists in the early 19th century was the Reverend Thomas Malthus, who argued that there were too many ‘unproductive’ poor people in the world, so regular plagues and disease were necessary and inevitable to make economies more productive.

British Conservative journalist Jeremy Warner argued (Daily Telegraph, March 11) this for the Covid-19 pandemic which ‘primarily kills the elderly’. “Not to put too fine a point on it, from an entirely disinterested economic perspective, the COVID-19 might even prove mildly beneficial in the long term by disproportionately culling elderly dependents.” Responding to criticism ‘Obviously, for those affected it is a human tragedy whatever the age, but this is a piece about economics, not the sum of human misery.’ Indeed, that’s why Marx called economics in the early 19th century – the philosophy of misery.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original, with all hyperlinks and charts, can be found here.