By Karen Lockney, Carlisle Labour member

We can start with the recent brutal murder in London, of a woman in an apparently random attack, her body mutilated and found in woodland, the subsequent arrest of a Metropolitan Police officer, a grief-stricken family speaking out. The name is on your lips of course, it doesn’t need spelling out – I’m referring to the murders of Nicole Smallman, and her sister Bibba Henry.

Household names? Chances are, it was a different murder to which you thought I referring, that of Sarah Everard. Like Sarah, sisters Nicole and Bibba were in London parkland late at night, on June 6 2020, after spending some time with friends. Their bodies were found having died from multiple stab wounds.

An 18-year-old man was later arrested, has pleaded not guilty and is now remanded in custody. Two Metropolitan Police officers were also arrested, and suspended from duty, charged with taking ‘inappropriate photos’ at the crime scene which they later shared with others. The allegation is that they sent a photos of the deceased women, and joked about abducting and murdering women. A further six officers are under investigation for receiving the photos in a WhatsApp group and failing to report them.

There isn’t a single reason

The question, of course, is why the murder of these two women did not receive the same attention as the equally tragic murder of Sarah Everard. There are several possibilities, and perhaps there isn’t a single reason. Some people point to the fact Everard was murdered by a serving officer, others to the tide of social media reaction during lockdown.

However, a dominant thread in the debate is the fact Nicole Smallman and Bibba Henry were black, whereas Sarah Everard was a middle class white woman. The mother of the sisters, Mina Smallman, has expressed her empathy for the Everard family, “You can’t begin to understand what it is to lose a child under those circumstances and then to have a further betrayal [by] the very organisation…we have an agreement with they will protect us.”

She has also expressed her view that both race and class are factors in the way her daughters’ murders were investigated and reported, that the Met did not immediately respond when she reported them missing, “I knew instantly they didn’t care because they looked at my daughter’s address and thought they knew who she was. A black woman who lived on a council estate.” With reference to the images shared by the officers, she said she was reminded of the “Deep South [in the USA] when they used to lynch people and you would see smiling faces around a body.”

We need as a society to make women’s lives safer

Clearly the murders of all three of these women are equally tragic, but the discussion around the comparative treatment of the cases illustrates the stark reality of the intersectional issues we need to understand and debate if we are, as a society, to find a way to make women’s lives safer, to make all our lives safer. Race, gender and class all intersect in this debate and the complexity of this has to be addressed if we are to make progress.

In the year to March, last year 207 women were killed in England, Scotland and Wales, meaning one in four killings were of women. Research from the Femicide Census, which collects information on male violence against women, calculates that 1,425 women were killed by men in the ten years to 2018, about one killing every three days.

Around 57% of female victims are killed by someone known to them, most commonly a partner or former partner (compared to 38% of men). Men are more likely to be victims of violence such as assault (1.3% of women were victims of violent crime in the year to March 2020 compared to 2% of men).

Increased call for support services during the pandemic

In the same period, 4.9m women and 989,000 men were estimated to have been victims of a sexual assault, including 1.4m women and 87,000 men who had been raped or faced attempted rape. (Figures from BBC report How many violent attacks and sexual assaults on women are there, March 19, 2021). In terms of interpersonal violence (IPV), women are significantly over-represented, and the year to March 2020 showed an estimated 1.6m women and 757,000 men experienced domestic abuse (ONS data).

It is important to note that men do experience domestic abuse from both male and female partners, the ManKind Initiative charity (www.mankind.org.uk) is a support service and useful source of information on this topic. There is much discussion on an increase in domestic violence during the pandemic.

The British Medical Journal recently reported that there has been a large increase in calls to support services and the police particularly in the UK, Brazil and Nepal, though a substantial fall in emergency department attendance for domestic and sexual violence (BMJ, 2021:372). ONS data also suggests it is difficult to assess accurately the picture during the pandemic for various reasons, but demand for support services has significantly increased.

Debate should not fade as news agenda moves on

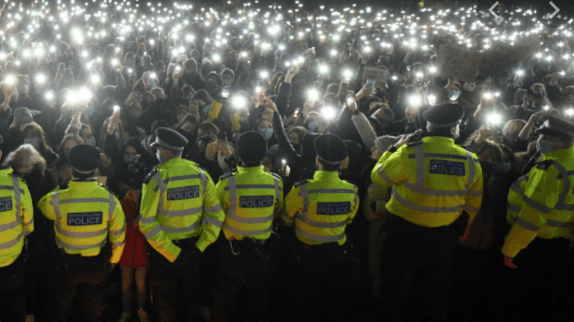

There is absolutely no doubt that society has a problem with violence against women and girls, and domestic violence in all its forms. The outpouring of emotion and anger on social media since the murder of Sarah Everard, and the policing of the protest on Clapham Common has thrust this issue into the spotlight, and it is clear that this is a debate that should not fade into the shadows as the news agenda moves us on to another crisis.

Whether the dominant narrative of the social media response gets to the heart of the issue is another matter, although the dominant response seems to put gender in the foreground over and above, rather than alongside race and class. For the Left, the response must ensure this intersectionality is considered.

Firstly, we need to look at the ways in which misogyny as a feature of women’s oppression is a feature of wider class-based oppression stretching back centuries. Many Marxist feminists resist the notion that male oppression of women is a natural state of affairs, based largely on men’s physical ‘superiority’ over women, and prefer (though some dispute his claims) an analysis clearly presented by Engels in The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State that the oppression of women came about historically, inextricably tied to the emergence of private property, agriculture and the dominance of the family unit.

It is possible to resist the received wisdom that violence is ‘natural’

This is worthy of another, longer article in itself for full exploration of different points of view, but the point is being made briefly here to highlight the fact it is possible (desirable for many Marxists) to resist the received wisdom that women’s oppression is to some degree natural or inevitable and must be seen in the wider contexts of oppression in general. (A useful article which gives a detailed overview of this debate is by Sheila McGregor in International Socialism).

Sandra Bloodworth in Marxist Left Review (2015, issue 10) argues that sexual abuse is ‘deeply rooted in the structures of capitalism’ and must be understood in this social context, and that violence against women can never be eradicated while capitalism rules. She is damning of governments seeking photo opportunities on White Ribbon Day, whilst simultaneously cutting budgets to social services and continuing a privatisation agenda.

This is an excellent article (available online) for those wishing to read more about a Marxist analysis of sexual violence and violence against women. Bloodworth explores in some detail the Marxist concept of alienation as a partial factor in the prevalence of sexual abuse.

She refers to Georg Lukacs’ History and Class Consciousness (1971) which argues that state bureaucracies and hierarchical institutions, ‘flatten all human relationships and deaden human empathy’, going on to argue that the “transformation of human function into a commodity reveals in all its starkness the dehumanised and dehumanising function of the commodity relation.” For Bloodworth, “People are turned into predators when they play an oppressive role in a hierarchy.”

Increasingly punitive state measures

She continues to explain Foucault’s analysis of human sexuality and argues that the state deliberately uses fear (of sexual violence) to oppress minorities and impose authority. She is concerned about increasingly punitive state measures which reflect hierarchies and privilege retribution, essentially undermining rights within a rigid criminal justice system, rather than provision of support eg through shelters and services.

These thoughts are particularly useful to us as we consider the irony of the heavy-handed policing of the Clapham Common protest. Ultimately the argument is that to combat sexual violence, we need to fight women’s structural oppression. And for Marxists, of course, that can only be done within and alongside fighting class oppression more widely.

What then is to be done? Resistance to cuts to support services is key, alongside equalities campaigns in the workplace and in society as a whole. I would also argue that we need a better understanding of the role poverty plays in prevalence of domestic violence.

A 2017 Italian study raised concerns that most killings of women took place in Lombardy, one of the most economically deprived area, arguing, “the fight against violence against women involves a struggle against capitalism”. It shows how Italy has one of the lowest percentages of women in employment in Europe (46%) and a poor welfare state in relation to childcare and care for elderly relatives. In UK contexts, the Child Poverty Action Group shows that poorer households are more likely to experience domestic abuse, with women on low incomes 3.5 times more likely to have this experience than women in better off households (British Crime Survey Home Office data).

A Marxist analysis, as I have suggested, requires engagement with the complexities of intersectionality and also a theoretical analysis of socio-political systems and hierarchical power dynamics. On the one hand, it feels incredibly complex, and I have been aware of this as I sit researching and writing this article.

“What is wrong with people?”

I set this level of complexity against my 13-year-old daughter’s straightforward questions on looking at the tidal wave of information and action coming at her in recent weeks (on her social media, in school assemblies, in chat with friends, on the TV), “Mum, why on earth would anyone murder another person like that? What is wrong with people?”.

I ponder what I am going to tell her about how to make her way safely in the world. I feel out of step with some of the response I see aired on social media. I agree with the ‘educate your sons’ line; that can only be a good thing, though that task seems huge. I still feel the need to teach my daughter to protect herself though, that isn’t going away soon.

I don’t have a problem, as many feminists have aired, with the #NotAllMen hashtag, or at least the sentiment behind it, and I don’t feel the need for men I know to put a post declaring their lack of intention to hurt any women and condemnation for men who do.

I can see why some feminists object to the hashtag, or welcome the well-intentioned posts, but for me, it’s blindingly obvious it’s a small minority of men who commit violence or abuse. I don’t feel entirely comfortable with the assertion that violence against women includes lower-level harassment, such as cat-calling, or at least not with the use of ‘violence’ as an umbrella term.

Harassment and violence do occur in the workplace

I absolutely call out real violence, and I absolutely call out harassment, but I believe they need tackling in more nuanced ways. I think a lot about these things as a woman, a mother and as a university lecturer; where I teach, a lot of women, including many young women are working all of this out.

I am also the Equalities Officer for my union branch and I look out for workplace safety, including from sexual harassment. I have worked in universities and schools for over 20 years now, I can honestly say I have never felt unsafe at work in terms of harassment or violence, and I asked several women I know the same in preparing this article, and all confirmed similar experiences.

That is not to say I don’t believe harassment and violence occur in the workplace; of course they do. I just believe it is important to acknowledge that not every woman experiences this. (This is not the same as other means of sexism in the workplace, for example in the gender pay gap or unequal pay, I am referring specifically to harassment and violence.)

There is a consistent line in some feminist comment on these matters since second-wave feminism in the 1960s, that we need to be wary of narratives that position women as victims, constantly wary of threat. I subscribe to this view. Not all women are able to fight back if they are on the receiving end of low-level harassment; they need support on a personal and structural level.

Women can and should call out wrong-doing

However, many women can and should call out wrong-doing and fight back, and I want to teach my daughter to be one of those women if I can; I don’t want her to live in fear. She absolutely knows that the men in her and my life are good people who would not hurt her or other women or girls, she doesn’t even need to question that, and it shouldn’t need a hash tag. She needs to be savvy about her safety though, we still live in that world, and she needs to be able to stand up for herself.

As these news events have played out, my mind turned back to a couple of incidents that formed my view of all of this as a young woman. One, age 19, I went to visit a school friend in her college in London and we walked back to her accommodation down a long, wooded drive, one foggy November Sunday around 4.30, getting dark. A man walked past us hurriedly, something about him caught my eye.

Later it transpired that one of her classmates ahead of us had been pulled off the path by a stranger and raped in the woodland. The police assumed the man we had seen was a suspect and we gave statements. A month or so later, we had returned to the North East for Christmas and the phone rang; they’d arrested a man for the rape, would we go down and identify him in a line up?

We got the train the next day. There was no glass, like in the films, we walked up and down a line-up. I wasn’t sure, my friend identified someone the police had clearly already decided was the rapist. “We know who did it; we just need an identification.”

Culture in sections of the Metropolitan Police

They offered us a lift back to Kings Cross and tried to invite us to a party instead, told us we were pretty, said they could find somewhere for us to stay the night. We caught the train home. I look back on this when I think about the culture in sections of the Metropolitan Police, even though it is now the 21st century.

In my second year at university, living in a student house in Manchester, a man was going around breaking into houses, entering young women’s bedrooms as they slept and raping them. He did it about seven or eight times before he was caught. One of these incidents was in a house over the road from us.

Some women have terrible stories to tell; terrible things happen. The stories I tell here do not compare to those some women live with, and I would not claim that they do. I tell them to show that I have always been aware of the danger, to know it is real and to know it needs to be tackled.

A complex picture and open debate is needed

Sending my own daughter out into the world is a process that is coloured with these experiences and attempts to rationalise and understand them. There are no easy answers. What I know is that this is a complex picture and open debate is needed if we are to understand. Men and women need to feel comfortable participating in this debate.

Not all women agree, not all men will agree. Social media is helpful in some ways but doesn’t allow sufficient space for the nuanced responses necessary. The Left needs to promote understanding of the contexts of women’s oppression within wider oppressions, not limited to gender, and not limited to race, but appreciating the nature of oppression more widely under capitalism and arguing for both theoretical and practical alternatives.