By John Pickard

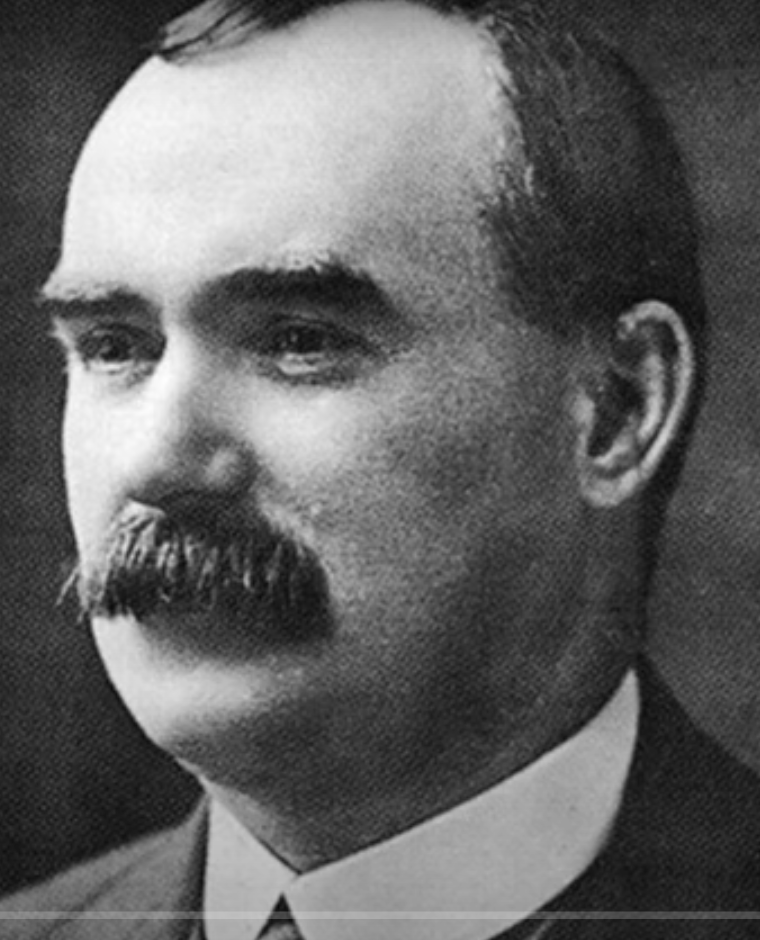

It was 125 years ago this week, that the celebrated Irish-Scottish socialist, James Connolly, launched the Irish Socialist Republican Party at a meeting in a Dublin pub attended by only eight people. That meeting in 1896 was an inauspicious start, but it marked a maturity in Connolly’s thinking which from that time came to mark him out as the single most outstanding socialist theoretician produced in the British Isles in that period.

Connolly’s ideas are relevant today and it important that serious socialists study them, because his name is so often used and his ideas so much distorted within the labour movement – and even more on its fringes – that it is worth all activists reading Connolly for themselves and making their own judgements. It is particularly in relation to the National Question in Scotland and Ireland that Connolly’s support is courted, whether it is deserved or not.

Years of struggle and furious activity

The ISRP founded on that day a century and a quarter ago was to only last a few years, but they were years of great struggle and furious activity and, on Connolly’s part, years of writing and setting down his socialist ideas. The ISRP has no organisational connection, and little politically, with the modern party with a similar name – the IRSP of Northern Ireland – although the latter may falsely claim for itself the legacy of Connolly.

Throughout his whole life, Connolly saw the struggle for Irish freedom from British control as one that was inextricably bound to the struggle of Irish workers against the landlords and capitalists of Ireland, and all those who masqueraded as ‘nationalists’ and Irish ‘patriots’, all the better to fool the workers into offering their political support. He waged an implacable struggle the whole of his life against the charlatans who shouted for Irish ‘freedom’ when what they really meant was their freedom to exploit Irish workers in the place of British capitalists. In Connolly’s view – and it stands out in all of his writings – there was no question of Irish ‘freedom’ as long as the system of capitalism and landlordism prevailed in that island.

Connolly was an uncompromising advocate of workers’ struggles and advanced the slogan, not of an Irish Republic, but of an Irish Socialist Republic, a big difference. He saw the working class as the key driver in achieving both social and national emancipation and an important element in that struggle was the unification of Protestant and Catholic workers.

Divide and rule a conscious policy of British Imperialism

Indeed, he argued that without a socialist policy to offer improvements in the daily lives of all workers, it would be impossible to counteract the deliberate fostering of divisions by the ruling class. Divide and Rule was the fundamental policy used by the British ruling class to underpin its control of Ireland North and South and, once perfected in the island of Ireland, it was put to use in many parts of the world.

There may only have been eight members at the founding meeting of the ISRP, but its programme, written by Connolly, shone out for its clarity and its boldness. Connolly wrote the first public statement put out by the party.

“The struggle for Irish freedom has two aspects”, it said, “it is national, and it is social. The national ideal can never be realised until Ireland stands forth before the world as a nation, free and independent. It is social and economic because no matter what the form of government may be, as long as one class owns as private property the land and instruments of labour from which mankind derive their substance, that class will always have it in their power to plunder and enslave the remainder of their fellow-creatures.”

The programme of the party included the nationalisation of railways and canals, the abolition of private banks to be replaced by the establishment of state banks, publicly owned depots in rural areas with agricultural machinery available to farmers, and a graduated income tax. It was a big improvement on the times for the party to also demand a restriction of the working week to 48 hours. Whereas most schools were owned and managed by the Catholic Church, the ISRP demanded “public control and management of National schools by boards elected by popular ballot for that purpose alone”.

National liberation bound up with the struggle for socialism

The whole thrust of the programme of the party was that independence, or the national liberation of Ireland, was bound up with the struggle for a new, socialist society. As Dermot Greaves wrote in his book, The Life and Times of James Connolly, “To proclaim, at a time when the socialists of oppressed nations were frequently taken to task for their ‘nationalism’, that the struggle for national independence is an inseparable part of the struggle for socialism, entitles Connolly to a foremost place as a political thinker.”

Perhaps the most famous passage of Connolly’s where he describes the link between nationalism and socialism is based on his writing in this period. “If you remove the English army tomorrow,” he wrote, “and hoist the green flag over Dublin Castle, unless you set about the organisation of the socialist republic, your efforts would be in vain. England would still rule you. She would rule you through her capitalists, through her landlords, through her financiers, through the whole array of commercial and industrial institutions she has planted in this country and watered with the tears of our mothers and the blood of our martyrs. England would still rule you to your ruin, even while your lips offered hypocritical homage at the shrine of that Freedom whose cause you betrayed.”

Open-air public meetings a regular feature

The ISRP took seriously the need for political education, and Connolly was to give talks and lead discussions on the ideas of Karl Marx, on the Communist Manifesto and on the Paris Commune. But it was no inward-looking debating society. It actively preached the ideas of socialism indoors and out. Open-air meetings were held regularly, as Greaves suggested, “on a scale Dublin had never seen before.” Adverts were put in newspapers for public meetings. It may have started out as a party, as one wag put it, “with more syllables than members”, but its influence grew rapidly.

When plans were put in place to celebrate Queen Victoria’s Jubilee on June 22, 1897, the ISRP organised widespread anti-royalty demonstrations in Dublin, through street meetings and rallies. These were suppressed and even brutally attacked by baton-wielding police. But it was working class Dublin that was protesting the royal spectacle, not the well-to-do, because the ‘official’ Irish Home Rule opposition either stayed silent (even on police brutality) or joined in the celebrations.

Despite oppressive police measures, as Greaves wrote, “the myth of loyal Dublin was destroyed.” It was actions like these that earned the ISRP the reputation as the most uncompromising left wing of the workers’ movement. In only a year and a half, Connolly was to write, the ISRP had gone from “obscurity to public recognition, and even approval.”

Paid the princely sum of £1 a week…sometimes.

Connolly, as the secretary of the ISRP, was supposed to be paid the princely sum of £1 a week, but even that wasn’t always available, and when money was spare it was often put into the publication of leaflets. But still, Connolly was able to travel around Ireland, as well as back and forth to Edinburgh, his home city, building support for the ideas of socialism. He spent three weeks in Kerry, for example, speaking at meetings, of small farmers and farm-labourers, caught up in an agricultural crisis.

In time, Connolly was able to secure a £50 loan from Keir Hardie, with whom he was in regular contact, so the ISRP could produce its own newspaper, the Workers’ Republic. At its launch, Connolly, who was always a prolific writer, explained the principles on which the newspaper was founded: “To unite workers and to bury in one common grave the religious hatreds, the provincial jealousies, and the mutual distrusts upon which oppression has so long depended for security.”

Unfortunately, and largely for financial reasons, the Workers’ Republic ceased publication just as the ISRP was beginning its first foray into electoral politics. The ISRP itself won a minority of votes in the North Rock ward of Dublin, where it stood, but elsewhere in Ireland ‘labour’ or ‘trade union’ candidates were successful.

Campaign against British support in the Boer War

The ISRP newspaper recommenced publication in May 1899, with Connolly as the editor, the main contributor, the compositor and, except where he could find some assistance, the printer as well. By now, the party had branches or supporters in Dublin, Cork, Belfast, Limerick, Dundalk, Waterford and Portadown and it launched a political campaign around the Boer War which had just broken out. In the press and in public meetings, the ISRP argued against support for the British government in its overseas imperialist wars and against the voluntary enlistment of Irishmen into the British Army.

The ISRP stance drew a red line between themselves and the Home Rule Party, some of whose spokesmen were even supportive of the British government. The Party came in for a lot more attention by the state and the police at one point raided the offices, smashing the press that produced the Workers’ Republic. The paper continued publication after that date, but it was never regular: more a case of quality rather than quantity.

In early 1900, in the new municipal elections, the ISRP did less well than previously, along with all other labour and trade union candidates in Ireland, to some degree as a result of a wave of pro-British chauvinism – even in Ireland – arising from the Boer War.

Guinness employees given the day off.

Later that year, the British Government decided on a visit to Dublin by Queen Victoria. Massive security measures were put in place. Special ships brought thousands of Harland and Wolffe workers from Belfast, to line the route of the procession in Dublin. Guinness employees were given the day off and a shilling added to their pay to enjoy the visit. Thousands of troops and police were put on full alert.

Despite a façade of relative calm in Dublin, where the city was so heavily-policed that serious opposition was difficult, the rest of Ireland was a swirl of protests and opposition. Even in England, on the Army training grounds in Salisbury Plain, there were riots between Irish and British soldiers.

The ISRP was firmly internationalist in its outlook and two of its members attended as delegates to the Socialist International Congress in Paris in 1900. At time when many of the leaders of that international movement were moving rapidly to the right, abandoning the Marxist views of its founders decades ago, the Irish delegation was firmly on the left flank.

Party split and effectively disappeared in 1904.

The ISRP period was the time when Connolly’s ideas matured into a rounded out socialist and class position. Despite his guiding hand and his indefatigable rate of work, Connolly was not able to gain a livelihood out of the ISRP. He was forced, more out of economic necessity than anything else, to emigrate to the United States in September 1903, where he spent over seven years as an organiser for the IWW. In his absence, and without his guiding hand, the party was riven with internal splits and personality clashes, effectively disappearing in 1904.

The legacy of the ISRP, in terms of its ideas and tradition, was resurrected by Connolly on his return to Ireland in 1910. He no longer worked around the party, which was long gone, but his socialist outlook and his implacably working-class orientation were unchanged, right up to his death after the Easter Uprising in 1916. As one of the leaders of the Easter rebellion, Connolly, although seriously wounded and having to be tied to a chair, was summarily executed by firing squad.

The outrage felt across the whole of Ireland over the British Army’s execution of its top prisoners started off a movement against British rule far broader and more sweeping than the Easter uprising itself. But that will need to be the subject of other articles. What is important for the moment is that we mark the foundation of Connolly’s ideas, particularly around the ISRP that he created, and that we continue to read and discuss his ideas today.