By Michael Roberts

Isabelle Weber is an assistant professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and the author of How China Escaped Shock Therapy. She recently wrote in the UK Guardian newspaper that price controls should be considered to deal with the inflation spike hitting many economies in the wake of the COVID crisis.

Weber’s piece was just 800 words long, but it provoked a squall of debate between radical post-Keynesian economists and more orthodox Keynesians over the effectiveness of price controls to control rising inflation of prices in general and to deal with the current inflation spike in the major economies.

Weber is author of the highly acclaimed book on the zigs and zags in the economic policy of the Communist leaders in China during the period of the country’s unprecedented economic rise. My review of her book can be found here. Weber comes from one of the more radical departments of economics in the US and is apparently a big fan of post-Keynesian authors like Minsky and Kalecki (but not it seems Marx). She also is a supporter of Modern Monetary Theory.

Prices rising fast internationally

Inflation rates have been rising in most of the major economies to levels not seen since the 1970s. Some mainstream economists have been arguing this spike in inflation is due to excessive demand by consumers who have huge piles of money given to them by governments during COVID (ie ‘quantitative easing’) and by fiscal stimulus programmes designed to spark an economic recovery. Much of these measures have been financed increasingly by central bank credit injections, MMT style. The mainstream view is that it is time to rein in these monetary injections with interest rate hikes and by tapering off quantitative easing. Post-Keynesians and MMT promoters oppose this and want to continue with fiscal boosts and monetary easing. So Weber offers an alternative policy to tighter monetary measures and fiscal austerity (ie more taxes and less spending to control rising inflation). It is price controls.

In her piece, Weber likens the current inflation spiral to just after WW2. Then even mainstream economists advocated price controls. Weber argues that: “Price controls would buy time to deal with bottlenecks that will continue as long as the pandemic prevails.” She quotes the much-revered post-war Keynesian economist JK Galbraith: He explained that “the role of price controls” would be “strategic”. “No more than the economist ever supposed will it stop inflation,” he added. “But it both establishes the base and gains the time for the measures that do.” So just a short-term measure then. But Weber then adds that “Strategic price controls could also contribute to the monetary stability needed to mobilize public investments towards economic resilience, climate change mitigation and carbon-neutrality.” In other words, not a short-term measure after all, but a key policy that would control inflation indefinitely so that public investment financed by central banks a la MMT does not have to be curtailed.

Mainstream economists erupted nastily to Weber’s argument. Orthodox Keynesian guru Paul Krugman was particularly scathing. That’s because it is a law of neoclassical economics that governments cannot buck markets and if controls on market prices are imposed by government, that will lead to significant imbalances of ‘supply and demand’ ie either shortages of supply and even outright recession. Let the market rule prices because you cannot stop the sun rising in the east, or if you do, there will be permanent darkness.

Sector price controls already exist

On one level this dispute is misleading. That’s because in many sectors of capitalist economies, price controls are already in operation. There are rent controls; transport fare price increase caps, and price caps on utilities like gas, water and electricity in many countries. Price regulation on private ‘monopolies’ and state industries can be found everywhere.

But this is not what Weber means by ‘strategic price controls’. Instead, price controls are offered as a policy alternative to control inflation compared to monetary tightening and fiscal austerity as the mainstream advocates. But price controls to control rising or high inflation in capitalist economies will not work precisely because inflation is determined by the laws of motion in a capitalist economy that are more powerful than controls. Sure, price controls on drugs or transport fares can play a role for specific sectors where perhaps just a few companies dominate the price, but because such controls just cover a sector and not a whole economy, they won’t be effective overall. Targeted price controls may not distort overall supply and demand movements in an economy but for that reason, they have little effect on overall inflation of prices, which is being driven by other factors.

Historical evidence of price controls

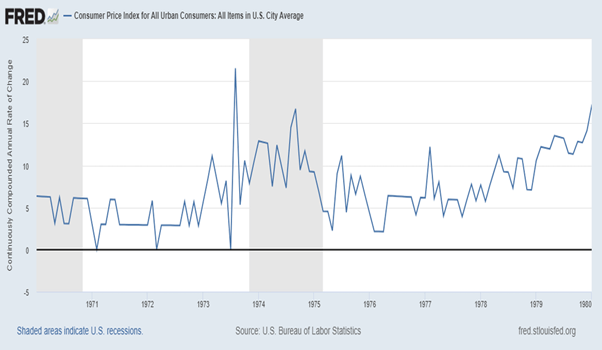

The historical evidence of overall price controls in a capitalist economy is that they either work at the expense of production by creating shortages or even provoking a recession. Take the 1971-4 price controls introduced under the Nixon presidency in the US. It is argued that they worked to control price rises for a while, but as soon as they were lifted in 1974, price inflation rose again. A paper by Blinder and Newton concluded that “According to the estimates, by February 1974 controls had lowered the non-food non-energy price level by 3-4 percent. After that point, and especially after controls ended in April 1974, a period of rapid ‘catch up’ inflation eroded the gains that had been achieved, leaving the price level from zero to 2 percent below what it would have been in the absence of controls. The dismantling of controls can thus account for most of the burst of ‘double digit’ inflation in non-food and non-energy prices during 1974.” Actually, during the period of price controls, inflation started to accelerate in 1973 as the US economy reached a peak of expansion alongside falling profitability and slowing investment growth. What lowered inflation in the end was the deep recession of 1974-5, not price controls.

Recently economists at the White House Council of Economic Advisors issued a paper suggesting that price controls could work just as they did after WW2. The White House economists reckon that “the inflationary period after World War II is likely a better comparison for the current economic situation than the 1970s and suggests that inflation could quickly decline once supply chains are fully online and pent-up demand levels off.” Yes, but exactly, if the ‘sugar rush’ of pent-up consumer demand falls back and supply bottlenecks are resolved, then inflation rates will probably subside. So how would price controls help at all?

Short term policy or long term policy alternative?

Like the White House, Weber says controls could be used in the short-term to get a ‘breathing space’ on inflation; but she is really advocating controls as a necessary long-term policy alternative to fiscal and monetary restraint, which is not the same. That price controls are seen as a long-term, even permanent, policy by Weber and the post-Keynesians is revealed by the other big bugbear of post-Keynesianism after fiscal ‘austerity’, namely monopolies.

As Weber says, “a critical factor that is driving up prices remains largely overlooked: an explosion in profits. In 2021, US non-financial profit margins have reached levels not seen since the aftermath of the second world war. This is no coincidence…. Now large corporations with market power have used supply problems as an opportunity to increase prices and scoop windfall profits.” So, you see, rising inflation is the result of ‘price gouging’ by monopolies. We need price controls on monopoly pricing power.

But it’s just not true that rising profits (margins) lead to inflation. As a study by Joseph Politano finds: “The rise in corporate profits is largely attributable to this increase in spending: money first went from the government to households in aggregate, and now those households are spending money and sending it to corporations in aggregate. The jump in aggregate corporate profits is no more responsible for the rise in inflation than the prior jump in household income.” Politano adds: “there is no causal analysis here. One could just as easily repeat this exercise by ascribing all inflation to the increase in income caused by the stimulus checks, because without good causal inference the whole thing is just conjecture about what “actually” caused inflation”.

False claim that wage rises cause inflation

Indeed, we could also claim, as mainstream economists do, that wage rises cause rising inflation because companies have to raise prices to sustain profitability. But there is no causal or empirical validity for this. A dose of Marxist theory on inflation shows that prices are fundamentally set by the value of labour time going into commodities on average and not by the components of that value in profits and wages. If wages rise, then profits fall and vice versa, at least on average, not prices. And the major capitalist economies are not dominated by ‘monopolies’ that can jack up prices as they wish. If that were the case, inflation rates would be continually rising, whereas from the 1990s to pre-pandemic 2019, inflation rates in the major economies were falling!

Monopoly capital is a term that does not really describe modern capitalist economies, just as ‘competitive capital’ did not really describe 19th century capitalism. Most sectors in capitalist economies have a small group of ‘oligopolies’ and a large group of small companies. Depending on the various weights of these two groups, prices will be driven by ‘regulating capitals’ (see Shaikh Chapter 7), which are usually in fierce competition with each other, within countries and internationally. Monopoly profits are not the cause of movements in overall inflation rates; only in some sectors where ‘natural’ monopolies exist and even there, competition and technical change can undermine monopoly control of prices over time.

The White House and Weber argument that price controls during and just after WW2 worked is really misleading. Then governments were in full control of the major sectors of the economy in order to direct them to the war effort. A war economy with the major companies and financial institutions working to a plan is nothing like the free-for all for the capitalist sector in profits and investment as in the current pandemic. Total price control in an economy would require total control by the state of the oligopolies over investment and production. And total control would only be possible by taking the oligopolies into public ownership with a plan for investment and production.

So when Weber (and it seems MMT-guru Stephanie Kelton) cite the example of successful price controls in Communist China in its early years, they are comparing apples with pears. Price controls won’t work to get inflation down without causing a recession in an economy dominated by the capitalist mode of production. Squeezing profits across the board by such measures will only lead lower investment and production growth.

Fears that ‘austerity’ is coming back

Weber ended her article with this: “We need a systematic consideration of strategic price controls as a tool in the broader policy response to the enormous macroeconomic challenges instead of pretending there is no alternative beyond wait-and-see or austerity.” Weber and Kelton and other post-Keynesians are raising price controls as an alternative to ‘austerity’ as advocated by the mainstream. And they are right to worry that ‘austerity’ is coming back. See this piece by Chicago economist, John Cochrane that blames inflation on excessive government spending.

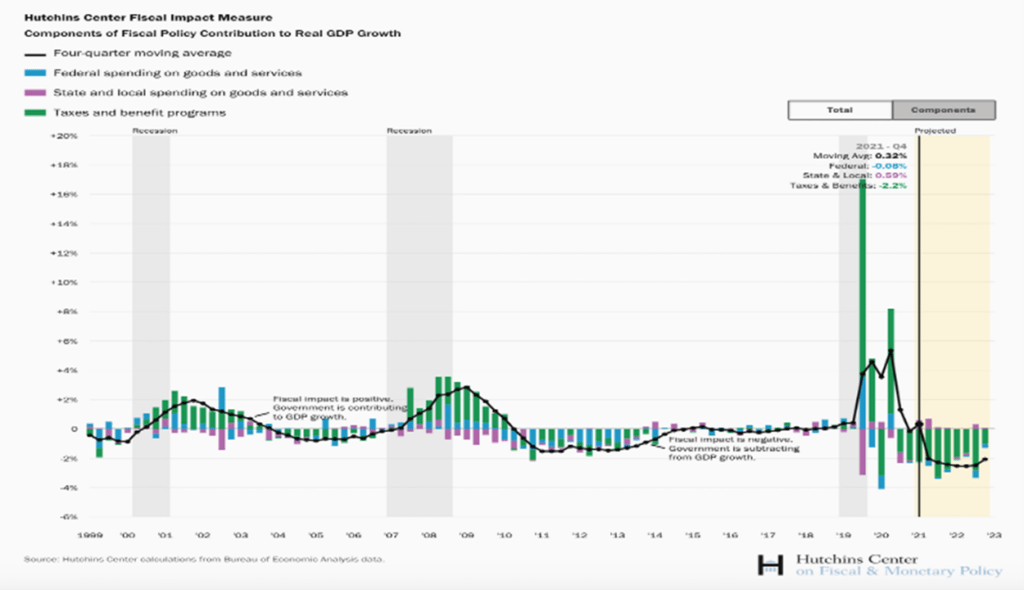

Already even under ‘profligate’ Biden, the government is set to take more out of the economy than it is injecting into it. According to the Congressional Budget Office, federal government spending is set to decline by 7% on average up to 2026 compared with 2021 levels while tax revenues are expected to rise by 25%. The US federal budget deficit will be halved in 2022 and kept down for the following years. So no Keynesian-style fiscal stimulus is planned – on the contrary. The graph below shows that US fiscal policy is no longer stimulating aggregate demand.

In my view, price controls cannot be an alternative policy to fiscal austerity in controlling inflation when the causes of inflation lie in the laws of motion of capitalist accumulation ie. changes in profitability, investment and output, not in monopoly power or monetary injections? In my view, the current high inflation rates are likely to be ‘transitory’ because during 2022 growth in output, investment and productivity will probably start to drop back to ‘long depression’ rates. That will mean that inflation will also subside, although still be higher than pre-pandemic. Price controls will be ignored.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original, with all charts and hyperlinks, can be found here.