By Sam Gleaden, Mental Health Worker

They are casting their problems at society. And, you know, there’s no such thing as society. There are individual men and women and there are families. And no government can do anything except through people, and people must look after themselves first.”

Margaret Thatcher, 1987. Interview for “Woman’s Own”

We are now living in a world which ever more resembles these infamous lines from Margaret Thatcher. Rates of loneliness are skyrocketing and general anxiety is on the rise. There is also a disturbing increase in people behaving in a hyper-competitive and self-obsessed manner, psychological traits which are evidenced to make us miserable.

The changes to the global economy since the 1980s have had a profound impact on our collective psychology. Thatcher, her global co-thinkers, and their supporters in big business, didn’t just want to make the rich richer. They wanted to force us to become more individualistic and “self-reliant”.

The transformation of housing policy has been a pillar of this process. Hugely inflated house prices have turned homes from somewhere to live, into a crucial economic asset, weakening homeowners’ reliance on society for security; while at the same time creating mass insecurity for the millions of young and working-class people that are now unable to access decent (if any) housing.

The Economics of the Housing Crisis

The importance of home ownership is deeply embedded in the culture of capitalism. Until the early 19th century, owning property was a requirement to vote. Property was a way of determining the ruling elite from those they ruled; those that are truly self-reliant, respectable and hardworking from those that are not.

Home ownership has also played a significant role in the cultural and political transformation of society since Thatcher. As part of a global move towards the neo liberal economic model since the 80s, publicly owned council housing that working-class people had fought to gain control over in the preceding decades, was rapidly sold off in the “right to buy scheme” (2.5 million homes were sold in 1980s). Across much of the western world the building of social housing was suppressed, while governments massively subsidised the mortgage market to encourage private ownership. These policies have continued today as the latest round of right to buy has recently been announced by the government.

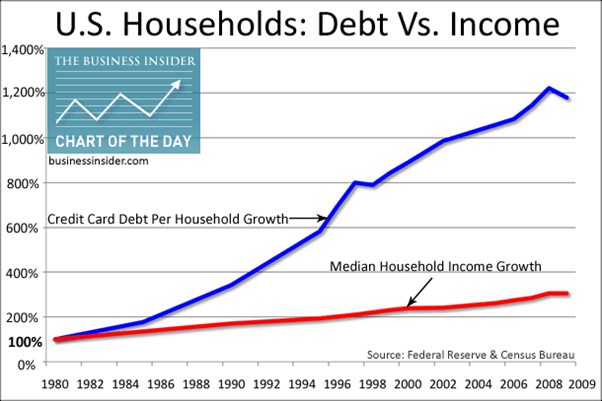

This process was facilitated by the aggressive deregulation of the Financial system allowing banks and building societies to borrow, create and lend unprecedented sums of money. Important changes in legislation allowed banks to lend money against the value of homes, meaning people could borrow considerably more to pay for day-to-day items (UK private debt increased from 40% of GDP in the 1984 to over 100% by 2007). This helped transform our global economic model to one where growth is based on higher levels of debt rather than increasing wages.

This trend is similar across the world but particularly the US and UK

Mortgage lending has now become a cornerstone of the global financial system as banks rely on this market for a huge section of their profits. Predatory mortgage lending on an industrial scale to poorer working-class people throughout the 1990s and 2000s, triggered the 2008 financial crisis.

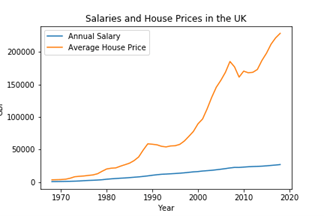

Although these changes initially meant more people owning their own home (from 53% in 1981 up to 71% of people in 2007), the opposite is now happening. Unprecedented sums of money pouring into the mortgage market has meant property prices have ballooned since the 1980s; Young and working-class people are increasingly priced out (only 62% own property now) as house prices have completely detached from wages.

40% of former Council Houses now private lets

The real result of the right to buy era is the rise of the rental landlord(40% of the originally sold-off council homes are now in the hands of private landlords). Those that are already wealthy are able to afford more and better houses while the rest of us are forced into expensive and shoddy rented accommodation.

This process has also massively contributed to the global rise of gentrification. Working-class people are being forced out of their communities by wealthier individuals as part of a negative spiral of inflated house prices and social cleansing.

In reality, modern housing policy is about supporting financial institutions, the construction/real estate industry and the wealth of private landlords – unsurprisingly 115 MPs are landlords themselves.

The housing crisis is having a devastating effect on our emotional well-being. This is not because people are now randomly choosing to behave in ways that create emotional turmoil but rather, they are reacting to the logic of our modern economy and housing market.

Breakdown of communities leads to loneliness

Rates of loneliness are climbing across the world; 45% of us now report feeling lonely to various degrees. One recent Gallup poll found that in 1990 the most common answer to how many people you can turn to in a crisis was two, today the most common answer is none.

The breakdown of communities due to the housing crisis is a key part of this phenomenon.

Gentrification in combination with the growing rental market is rapidly eroding our sense of community. Areas that increase in rental accommodation also describe an increased sense of loneliness.

Research shows clearly that it is the quality of human connections and not the number of interactions which relieves a sense of loneliness. Renters are less likely to stay in an area long enough to make long-lasting connections. It’s no surprise a recent study found that renters were twice as likely to suffer from loneliness as those who had long-term tenancies.

Another important aspect is our sense of identity and belongingness which we largely derive from our connection to a wider community. Again, research shows that renters are especially vulnerable to feeling low levels of belongingness which can eat away at self-worth and identity.

How many people do you know that now live far away from work, with those they have never met, in an estate or area where no one knows, or speaks to each other?

Gentrification is also linked, as communities which have formed over decades are torn apart. Unsurprisingly, communities affected by gentrification have been found to have less social cohesion. There is remarkably less community activity and people report feeling like strangers in their own neighbourhoods, especially those originally from the area.

Rising anxiety levels

As well as our growing isolation, a lack of housing security is contributing to the rise of anxiety levels. One in five of us has experienced mental health issues because of housing problems, according to a report by Shelter. This is down to a mixture of poor housing quality, fears of safety and increased rent payments.

The fear of eviction is now a standard reality across the world, particularly since the 2008 crash. This has been exacerbated further by the economic effects of covid with hundreds of thousands in the process of being evicted in the UK and 1/5 of renters at risk in the US.

Research in Sweden found that individuals facing eviction were four times more likely to attempt suicide. Another study in Spain shows that 89% of women and 85% of men report having poor mental health, much higher than that of the general population (19.5% and 14.5% respectively).

Those already more vulnerable to poor mental health often end up in poorer quality housing which reinforces their mental health issues. In my last role in mental health outreach in Kensington, one of London’s worst boroughs for housing, the majority of the service users had severe housing issues. Anti-social behaviour, rent payments or squalid conditions stopped many from recovering. Those few lucky enough to secure better housing saw a clear improvement.

Individualism – looking after number one

We are bombarded with messages from advertising, media and politicians that owning a home is a marker of true success. This is tied to our modern consumer culture where self-esteem is derived from social status and the possessions that symbolise this status; bigger and better houses equals being a better person.

This culture of competitive consumption, which modern housing has helped to explode through the expansion of credit, has been evidenced to make us deeply dissatisfied.

Surveys show that those who fail to own their own home feel extreme “status anxiety”- a form of anxiety stemming from not feeling worthy. Often people who don’t end up owning property are stigmatised as “failures”.

Our culture wants to blame economic issues on traits of “self-reliance” and “thrift” rather than the rigged housing market. A well-published poll recently found rather comically that 48% of older Brits blame young people’s dwindling home ownership on spending too much money on Netflix and coffee rather than house prices.

Not In My Back Yard

As the amount of economic support, the government gives has decreased, along with less housing itself, there is now a natural pressure on homeowners to worry about the value of their property. More than just a home, property is now an incredibly important asset which has to act as a pension, inheritance to children, and a means to borrow money.

This has led to something called NIMBYism (Not in my Back Yard) in the USA and a similar culture in the UK. This obsession with house prices means many become worried about lower-income people joining a neighbourhood, or anything that may devalue an area such as a homeless shelter, ethnic minorities or Covid testing sites.

As economist Noah Smith has argued, this culture stems from a scarcity mentality whereby the lack of economic security in society pushes people towards fearful and selfish behaviour. The political expression of this is a tendency for homeowners to vote for political parties that protect those with economic assets like housing, even in areas which are relatively poor. This has always been the political aim of housing policy as politicians looked to secure a voting base to fight against the organised workers movement.

What can we do to fight back?

We need to rediscover the collective militant action that originally won social housing. In reaction to landlords demanding a 25% increase in rent, an unprecedented mass rent strike in Glasgow in 1915 led to the first rent control legislation. Action like this, along with the fear of revolution after WW1, pushed the government into the Addison act of 1919, resulting in the first-ever mass building of social housing.

Today we have seen similar types of activism being successful in fighting the current housing crisis. In Berlin last year a mass campaign won a referendum to take back up to 240 thousand houses from exploitative private housing companies and back into public ownership.

Worker-led action can do more than just provide the security owning a home gives us, it can rebuild our very sense of community. When we engage in collective struggle, we form bonds which can break down the emotional disconnection capitalism creates.

One moving example of this comes from another housing campaign in Berlin. Kottbusser Tor, or Kotti as it’s known locally, is a poor district of Berlin. It contains some of the most marginalised groups including Turkish immigrants, the LGBTQ+ community and left activist squatters.

Before the anti-eviction campaign in the early 2010s, the community was deeply divided. It would be common to see homophobia from the Turkish to LGBTQ+ community and Islamophobia in reverse. The mental health of the residents was also decimated due to anxiety and isolation. Through the evictions campaign, the community came together not just to win rental rights but to become a true ‘home ‘for everyone. As one resident of Kotti said; “I’ve gained so much more than lower rent, to realise how many beautiful people are living around you, as your neighbours.”

Breakdown of the free market model

The free-market housing model that was designed to keep a large voting base for the Conservatives and other pro-business parties globally, is now breaking down. The very logic of the housing market towards greater dislocation of working-class people, and obscene concentration of wealth at the top of society is producing the political fuel for change.

Acorn and the London Renters’ Union (LRU) are examples of UK-based renter’s unions building mass campaigns to beat back landlords and win public housing. LRU developed a successful campaign to remove section 21, which previously allowed landlords to remove” not at fault” tenants without notice. Mass participation in organisations like these are going to be vital in reclaiming quality housing as well as rebuilding our sense of community.

The logic of the market under capitalism inevitably leads to economic and emotional instability. Huge sums of wealth and resources concentrate at one end with poverty and despair at the other. To secure housing as a human right, working people must have wider political representation to move beyond our capitalist profit-seeking system which only serves the interest of big business. Struggles within the renters’ unions, but also wider trade union action now emerging over pay, show the way forward. We must go further than previous generations whose reforms to the system have been eroded away, and instead fight for a socialist economic model which serves the needs of everyone.

From Sam Gleaden’s blog ‘The Sane Society; Capitalism and our Mental Health Crisis’. The original with all hyperlinks can be found here.