By Sam Gleaden

What if the very way that we understand mental illness is also a major contributor to our society’s mental health crisis?

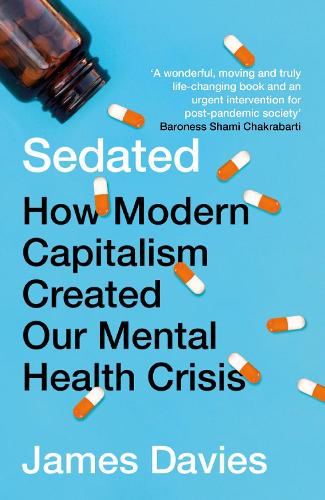

In Sedated :How Modern Capitalism Created Our Mental Health Crisis, James Davies argues that it is not only our dwindling public services, or growing economic inequality that is pushing people to emotional breaking point. Davies claims that the way our culture conceptualises “mental illness” reinforces suffering by blaming the individual for their distress rather than society.

Sedated inks the seismic shifts in the economic model of the 1980s to free-market fundamentalist ideas to changes in how we diagnose, treat and conceptualise mental health. It also looks at how all aspects of our lives have radically changed in the past 40 years and the pernicious effect this has had on our well-being.

In this article I want to highlight some of the most important points of Sedated while also arguing that the social causes of distress go deeper than just the economic ideas of the past 40 years.

New Capitalism

There are two distinct models of Capitalism which Davies refers to in Sedated. Firstly, the period between the Second World War and the 1970s which he refers to as the ’Golden age of capitalism’( also known as the ‘social democratic’ period). This was called the Golden age for good reason; It was the longest economic boom in capitalism’s history with unprecedented rises in living standards and economic equality.

After the Second World War, large sections of many Western economies were either owned by the government (nationalised) or managed more directly, with greater regulation over previously troublesome sectors (such as banking and finance). Working-class people had a stronger influence over living standards via massive trade union membership with collective bargaining for wages. Strong welfare systems were put in place to offer social housing, universal healthcare, and social security for those unable to work.

This model began to deteriorate under a series of economic crises in the 1970s leading to a new set of right-wing economic ideas and politicians determined to ‘fix’ the issues. Margaret Thatcher’s victory in the UK in 1979 and Ronald Reagan’s in the USA in 1980 set about a return to more classical forms of capitalism. Davies calls this ‘New Capitalism’ but it is commonly known as ‘Neo-liberalism’.

Neo-liberal thinking prioritises the growth of the private sector via privatisation and lowering the tax burden on the wealthy to allegedly unleash business investment. It was believed that the larger government intervention of the ‘Golden Period’ was both ruining the stability of the economy and importantly, the character of individual citizens, leading to working class greed and over-reliance on the state.

Davies specifically points out through interviews with leading conservatives, Thatcher’s dream was to change the hearts and minds of British people via the new economic model.

She wanted to force us to become more self-reliant, hard-working and individualistic as she saw these values as key in protecting our ‘freedom’ from the authoritarianism of the socialist nanny state. Big business overwhelmingly supported Thatcher in these goals because both the economic and behavioural changes were necessary for the new ‘neo-liberal’ model of capitalism we now have today.

Mental health system under new capitalism

“Sedated” shows how neo-liberal individualistic ideology and the power of big pharmaceutical companies has infiltrated our mental health system. This has driven it towards a crude medicalised model which blames individuals for their distress.

This medical model of mental health says that mental illness stems from genetically based neurotransmitter “chemical imbalances” of the brain, such as dopamine or serotonin, which are critical for regulating mood. Even the updated ‘bio-psycho-social’ model, which factors in social circumstances, says that social stresses like trauma only act to “trigger” this underlying illness.

The term “medical model” or “medicalised” model of mental illness was coined to describe how psychiatry has tried to treat mental illnesses like physical illnesses.

One fascinating insight Davies offer about Psychiatry is its almost unique level of incompetence as a medical field. Research from Harvard has shown that unlike nearly all other domains of medicine, where there has been an exponential increase in positive patient outcomes, psychiatry has flatlined since the early twentieth century. The study showed that between 1895 and 1955 patient recovery rates from mental health issues were approximately 34.5%, with a small increase in the post war period, then falling again in the 1970s to the same 34.5% figure.

How has such consistent failure been allowed to continue?

Diagnostic failure

One major contributor is our failed diagnostic system and the type of care it informs. Unlike most physical illnesses, mental health diagnosis are based entirely upon a description of people’s symptoms.

With a physical illness, a doctor will start with symptoms, such as a cough, rash or frequent urination; and then move to look for underlying biological proofs determining specific illnesses such as a blood test.

With mental health, illnesses have been entirely theorised, and then later diagnosed via descriptions of symptoms alone. For example, the way a doctor diagnoses schizophrenia is by looking at the diagnostic manual for a set number of symptoms described, such as hearing voices or delusional thinking.

However, this causes issues when the displayed symptoms overlap with the symptoms of another mental illness. Individuals are often given multiple diagnoses in a lifetime, with no real scientific way of testing for a specific illness, or if these illnesses truly ‘exist’ in any meaningful way at all.

This isn’t to say that mental health issues or specific symptoms don’t exist, they clearly do, but that they are not signals of an underlying ‘illness’ but a natural human reaction to challenging circumstances.

In other words, in psychiatry’s attempt to be more “scientific” our entire method for understanding mental distress is based on an intellectual house of cards. Psychiatry today reflects physical medicine 200 years ago where illnesses could only be diagnosed from symptoms such as coughing or frequent urination. The heritage of this we see today in modern medical diagnostic labels; for example diabetes and the much rarer diabetes insipidus share their name not because of their biological causes but due to their shared symptoms of extreme thirst.

Today, many in psychiatry , as well as those that I’ve personally worked with, generally agree this system of diagnosis is faulty, but are not clear on how to improve it.

Big Pharma and Psychiatric medication

Both “Sedated”, and Davies’ previous book, “Cracked: Why Psychiatry is Doing More Harm than Good”, look at the impact the pharmaceutical industry economic dominance has had over psychiatry.

One outcome of the “medical model” is that mental illnesses are perceived as chronic. They are only fixed by altering the “chemical imbalance” in your mind with psychiatric medications.

Psychiatric medication has multiple advantages as a method for dealing with distress from the point of view of big business and politicians.

- It is an incredibly profitable industry contributing £8.4 billion to UK GDP each year.

- Its relative ease at distribution offers an apparently cheaper alternative to more long-term individual therapy or community care that would be necessary otherwise.

- The medical model of mental illness acts as a cover from social causes of distress.

Although playing an important role for many in their recovery. There is growing evidence of the long term damage that the extensive use, and over subscription, of psychiatric medications can make. Recent evidence consistently shows that long term use of medications such as antidepressants (usually diagnosed for anxiety or depression) and antipsychotics (usually for psychotic illness like schizophrenia) both actually hinder recovery from mental illnesses as well as harming the individual via potential side effects such as changing the structure of the brain.

“Sedated” also explores how the pharmaceutical industry has been aggressively deregulated in the post-Thatcher era in the name of profitability. This has allowed them to exaggerate the effectiveness of psychiatric medications while underplaying the harms. Big pharma also funds the majority of psychiatric university research across the globe meaning there is a vested interest in promoting this disease based model of diagnosis.

Therapy services

This medicalised model within a ‘neo-liberal’ society has also affected therapy services on offer in the NHS. In the past 14 years expansion of a therapy service called IAPT (Increase Access to Psychological Therapies) has been created. However, the type of therapy offered, alongside its underlying goals and regulation, has left IAPT open to many criticisms.

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), the therapy primarily offered on IAPT, has been criticised for being far too short term to be effective for most patients. As with the rest of the medical model of mental health care, it often neglects life events and objective circumstances, instead seeing the answer in fixing ‘irrational’ thinking through specific techniques.

CBT works well where there is a genuine opportunity to help raise emotional insights for behavioural changes. However, for many people IAPT’s CBT programme cannot incorporate deep seeded trauma or challenges that have an external cause. Many psychologists have also argued CBT simply acts to reinforce defence mechanisms to help “manage” the “illness” rather than get to the root of the issues.

Another issue is that the outcomes of therapy are measured by IAPT itself. IAPT claims to significantly help 46% of patients. However, critical research has found that this data removes the patients that leave half way through therapy because they do not find it helpful (approximately 50% of all patients). The more realistic figure of 23% recovery you’re left with is also approximately how many people recover from depression without any mental health interventions at all.

This focus on short-term results seemingly at the expense of creating a more holistic service that offers a range of long term therapy is also rooted in our economic model.

Modern public services have been forced into a target driven model of care, emulating the private sector in the belief this will increase performance. The IAPT model was sold to the New Labour government as a way of encouraging people to get back to work and off the benefits bill. It is therefore designed to see unemployment as something to be solved by “helping people to think positively and rationally”, rather than an issue of the structure of our ‘neo-liberal’ economy which actually accepts a level of unemployment as necessary.

Davies gives some rather dystopian examples of modern jobcentre CBT courses which are supposedly designed to encourage people to find work, but instead act as a form of institutional gaslighting which blames people’s “irrationality” for their unemployment.

Neoliberalism and everyday life

As well as exhibiting the impact that neo-liberal economics have on the mental health system, “Sedated” shows how all aspects of our life are affected by the changes towards the neo-liberal model.

There are the obvious stresses that come from ever-worsening living standards. Changes in the structure of our economy mean we are now working longer hours, changing jobs more frequently and commuting further to work, with 5 million people now working on insecure temporary contracts. All of this is in order to keep wages low and working hours high so businesses can increase profits.

However, it is not just economic and material factors that make work miserable. Many are finding their jobs increasingly meaningless and boring. Study’s show that two thirds of Brits report that they had no positive experience at work; either hating it or were disengaged. With 55% reporting regular burnout due to excess targets and overtime, and 40% saying they felt their job had no meaningful impact on the world at all. Davies shows how these issues of dissatisfaction have increased markedly in the past 40 years.

One of the methods companies have used to deal with this growing workplace distress has been the use of well-being organisations such as Mental Health First Aiders (MHFA). These companies are hired to provide workplace training for some staff who are then instructed to look for signs of mental distress in the workplace, directing that person to professional care.

Although this may sound entirely positive at first, MHFA also follows the highly medicalised individualistic model of mental illness. This means that the location of the distress is always found to be with the individual, not their environment. Regardless of your working environment, bullying bosses, or your targets being unattainable, the answer is always “mental illness”. Sedated also shows this ideology has come into our education system where children’s understandable reactions to stress is diagnosed as a mental illness. For example, a child dealing with ever increasing extreme exam pressure is said to have Generalised Anxiety Disorder and put on medications.

Cultural values

‘Neoliberalism’ is not just a set of economic ideas but also a value system. As Thatcher made clear in interviews quoted in “Sedated”; Neo-liberal ideals see humans as fundamentally individualistic, competitive and at our greatest when striving to better ourselves.

Our modern economy also needs people to act as good consumers in the free market who want to ‘better themselves’ by purchasing more, as well as competing with each other to sell themselves to employers. These hyper-competitive ideals and competitive structure of our economy lead to very peculiar forms of social relationships which play havoc with our mental health.

The first effect Davies points to is the increase in levels of materialistic values since the 1980s. “Materialism” here means an increasing prioritisation towards the ownership of possessions such as cars, houses or clothing; particularly those which symbolise social status. This is closely linked to seeing our self-worth not deriding from our innate human characteristics but from our place within a social hierarchy.

“Sedated”shows ample evidence of a steady increase in people having materialistic values since the 1980s. There is also strong evidence that those who rate themselves as more materialistic are also much more likely to have diagnosed mental health disorders and generally have less life satisfaction on a number of different measures.

Finally, ”Sedated” argues it is not only the gathering of possessions for status which is harmful but the emotional consequences of social inequality itself.

Drawing from the work of Richard Wilkinson and Kate Picket, Davies shows how societies with greater inequality create citizens with greater ‘status anxiety’. Whereby people feel an increasing pressure to match a set of social ideals representing social status. Wilkinson and Picket use a 2014 viral article in which a young woman describes how overwhelming she finds social situations due to the pressure of keeping up appearances “every act from choosing clothes to making small talk is a fear based defence against criticism”.

Up to 70% of people now admit they would rather prefer to stay at home watching TV than to go out at the weekend to socialise, even with close friends. Although this clearly won’t all be down to “status anxiety”, Wilkinson and Picket’s research displays how “status anxiety” creates greater feelings of distrust and isolation in multiple aspects of our life as everything we do becomes a judgement of our worthiness.

We see this culture played out on social media with the “Instagramification” of everyday life. We are encouraged to present idealised highlights of our lives in order to chase social approval and validation from others. This is also used to sell us products via influencers also presenting a flawless life image we are supposed to strive for. Research has shown that this barrage of negative upward comparison to other people is a massive driver for poor mental well-being.

Is Neo-liberalism or Capitalism the problem?

Throughout “Sedated”, a compelling argument is made that the “neo-liberal” model is to blame for our current mental health crisis. There are regular favourable comparisons made with the post Second World War ‘Golden Age’. Although this period was undoubtedly more progressive in many ways than today, there are issues with this type of comparison.

Many of the problems that Davies outlines with modern society have been documented in the post Second World War era. For example, one 1960 study looking at mental well-being in a middle-class district of New York found that ¾ of society displayed symptoms of distress that could be categorised as mental disorders. Additionally, Many of the key theorists cited in “Sedated”, were analysing the problems of inequality , consumerism, or the stigmatising of mental disorders from this same period. In other words, the issues we have today were still a major problem in that ‘Golden’ period too.

Capitalism is a system built on the domination of working people by Big Businesses that overwhelmingly own and control our economy. Any form of capitalism will necessitate some level of inequality, oppression of minority groups, soulless employment, consumerism etc. as these are all necessary in running a profit-driven economy.

To idealise a return to the post-war period is to not understand that it was not just a set of ideas about how to run society, but a particular historical moment with very specific factors allowing its existence. The most important of which being the massive levels of organisation and radicalisation of working people, the fear of the spread of communism from the Soviet Union mixed with perfect conditions for economic boom created by the destruction in WWII.The post-war ‘Golden Age’ system failed due to having the same fundamental features of a capitalist economy, such as the tendency for global economic boom and busts.

Capitalism’s periodic crises leading to economic and political instability can’t be resolved by simply turning back the clock to the ideas of a previous era. This is not to say that its not possible to fight for progressive reforms within our neo-liberal system; but that these reforms will be temporary as the capitalists class will fight back to restore their profits and will not be able to resolve the deeper systemic issues already outlined.

For the type of society that Davies argues could potentially eliminate the majority of the unnecessary mental distress, we need to therefore move beyond capitalism entirely to a socialist system (the potential for this, how we come about it, is another argument entirely which I wont go into detail here).

However, the current medicalisation and individualisation of mental distress is a crucial problem.

Seeing mental distress from the perspective of what has happened to you, and your current life circumstances is clearly a better model than creating false diagnosis based on just symptoms.

A potentially useful alternative framework which incorporates these ideas is the Power Threat Meaning Framework (PTMF).It is an alternative to the medical model of diagnosis which is explicitly political. Rather than seeing the symptoms of peoples distress (such as depression , self-harm addiction etc.) as the signs of an underlying ‘mental illness’ it reframes distress in the context of the issues created by our society as they filter down to affect us individually.

PTMF, and more socially context-focused methods like it, have the advantage of allowing the individual to see where their distress stems from as well as de-stigmatizing the distress by framing it as a normal response to challenging circumstances.

This is distinguished from today’s ‘medical model’ which sees the deep suffering of huge swathes of society not as a trigger for personal or political change but instead that millions of people are broken; the only option given is to medicate, distract or “sedate” ourselves from our emotions.

With this in mind, the current mental health crisis represents both a challenge and an opportunity for the political left. Firstly, to radicalise millions of people who are affected by mental distress by explaining its overwhelmingly social causes. Secondly, to act as a genuine counter-cultural movement to the poisonous individualising of mental distress which can promote a de-shaming de-stigmatising message while giving a genuine opportunity to change our circumstances. Finally, the more progressive parts of the psychology/psychiatric profession should be organising, and turning towards organisations of the labour movement, such as trade unions, to help promote this message in a mutually beneficial manner.

From Sam Gleaden’s blog “The Sane Society: Capitalism and Our Mental Health Crisis” The original can be found here