By Cain O’Mahony

After Ramsay McDonald went to the King to form a new ‘National’ Government, over the heads of the big majority of the labour movement, he quickly moved to have parliament dissolved and have a general election. Only three weeks were allowed for campaigning.

[Part One of this article can be found here]

Just as we saw with the nonsense peddled by the media and Labour right wing about Jeremy Corbyn, so the Labour Party had lie after lie thrown at it, all the time with the Tories and McDonald claiming the country was on the brink of financial collapse. McDonald and many National Government candidates appeared on election platforms waving wads of the inflationary Deutschmark notes from the Weimar Republic, saying this is what would happen under Labour.

The most outrageous, ficticious smear was made on the eve of polling day, that Labour was planning to seize the small savings of millions of people held by the General Post Office Savings Bank, the only savings bank most workers had access to. The Manchester Guardian described the ‘election’ as: “The shortest, strangest and most fraudulent Election campaign of our time…”

With Tory and Liberal voters voting as one, and with many Labour voters confused by ‘their’ Labour Prime Minister calling for ‘national unity’, it was a landslide for the National Government. As JR Clynes put it, “It was more like a stampede by a scared and perplexed public than a General Election.” (The British Labour Party)

Arguments in ILP for disaffiliation

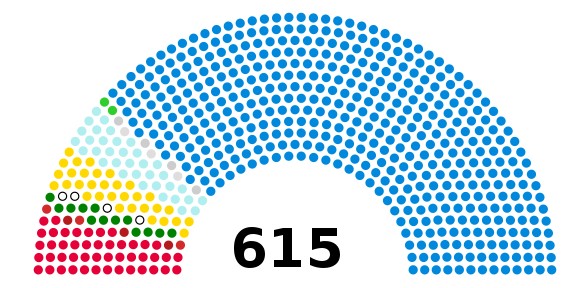

Not surprisingly, Labour was slaughtered. It returned only 46 MPs, of which three were ILP from their bastion of Glasgow. McDonald’s betrayal and now the collapse of Labour only furthered those in the ILP arguing for disaffiliation. It appeared that there was nothing to lose now, that the ‘parliamentary’ experiment had failed.

At the ILP’s 1932 conference in Bradford, it was agreed to split from Labour – it wasn’t unanimous, with around a third of delegates very hesitant. Even so, the ILP looked in a strong position, with nearly 17,000 members, an electoral base of over 100,000 voters, three MPs and strong support in Glasgow, Bradford and Lancashire. Its membership was over five times as great as the membership of the Communist Party.

In the disastrous 1931 election, the ILP had returned more candidates than the Labour Party in Scotland. It had an extensive organisation at both national and local level, a well-regarded national journal, supplemented by many more local publications. Many believed they had prospects of building a fresh, powerful and influential movement.

But the ILP ran into trouble immediately because it committed the cardinal sin of not being clear on why they were splitting for. They were united in what they were against – Labour right wing’s gradualism and bureaucratic measures – but now free of that, the glue that had united them came apart and they descended into factionalism as they fought over the best way ahead.

There were two main schools of thought. One faction, the Revolutionary Policy Committee (RPC) wanted to become an open revolutionary party, linking up with the Communist Party to form a ‘United Revolutionary Party’.

Stalinism and the Communist Party

Those opposed to this road formed the Unity Faction. They said the RPC were moving in advance of the actual consciousness of the labour movement. They wanted to still orientate towards the labour movement, and that the ILP’s role was to act as a socialist centrifugal force in both the labour movement organisations and in Parliament to draw the best left wing elements in the Labour Party to them. At the same time they wanted no truck with the Stalinism of the Communist Party, currently going through its ultra-left phase of Stalin’s ‘Third Periodism’, which dismissed any on the left who did not follow the Communist Party line as ‘social fascist’.

So within a year, the one party had effectively become two.

The bitter infighting only worsened. When the Unity Faction failed to overturn the RPC at the 1934 ILP conference, they in turn split and factionalised, with the leadership group splitting from the ILP to form the Independent Socialist Party, taking much of the Lancashire membership with them. And so two became three.

The triumphant RPC faction now wasted two or three years in a fruitless attempt to link up with the Communist Party. All the time, the ILP membership was haemorrhaging, with most drifting back to the Labour Party. Membership fell to 11,000 in 1933, 7,000 in 1934 and 4,300 in 1935. Indeed, by 1935, the key supporters of the RPC had collapsed into the Communist Party.

The sister of such indulgent factionalism is sectarianism. The closer they moved towards the Communist Party, the more they became infected with the ultra-left line of ‘Third Periodism’. The ILP became more isolated from the wider labour movement – it didn’t just leave the Labour Party, but instructed its members to cut off relations with the Co-operative movement too (a large movement in the 1930s).

Sectarian hostility to Labour Party increased

It said that all members should cease any local campaign work with the Labour Party; and to even opt out of paying the political levy to the Labour Party in the affiliated trade unions. As with the Communist Party, for the ILP, the Labour Party became Public Enemy Number One.

This sectarian hostility saw them Increasingly standing against Labour In elections, regardless of fears that they would split the vote, and when they did it was dismissed in the most light-minded way. This was graphically demonstrated in a local council election in Norwich, where the ILP candidate split the vote in this Labour stronghold and let in the Tory. The local newspaper reported that the ILP candidate was:

“ … pleased he had been the instrument by which the Labour candidate was kept out in the Catton ward… [as] he preferred to see a successful Anti-Socialist who in a straightforward fashion declared his position… rather than the underhand tactics of the Labour Party locally and nationally” (Eastern Evening News, 1 November 1933).

With such sectarianism comes the dogmatism of ‘principle’ – their sectarian approach leads them into a cul-de-sac of a self-imposed barrier of ‘revolutionary’ purity; the road they have taken is infallible and there can be no room for manoeuvre on tactics or orientation to the labour movement. To do so would be to admit they had made a mistake. When some ILP members suggested returning to the Labour fold in 1936, they received short thrift from the leadership, with an editorial in their paper thundering:

“ We can only enter the Labour Party by surrendering our revolutionary attitude, by standing at elections on a reformist programme and by promising obedience to the Labour Party Whip in the House of Commons. For a revolutionary Socialist that means surrender!” (New Leader, 5 June, 1936).

ILP increasingly seen as an irrelevance

With such sectarianism comes isolation from the real class struggle. Not that the labour movement were much troubled by the machinations of the ILP in the battles of the 1930s. They increasingly saw the ILP as an irrelevance. As one ILP member later lamented:

“ After the 1931 catastrophe we made the mistake of leaving the Labour Party voluntarily. So naturally the workers concluded we were people who liked to be isolated “ (Walter Sawyer, Letter to Controvery, February 1938)

Indeed, the ILP’s isolation and internal navel-gazing meant they were oblivious to the processes underway in the Labour Party. Far from being buried, the Labour Party was revitalised. It was rallying and moving sharply to the left. McDonald’s betrayal had shocked the ranks of the Labour Party from top to bottom, with, reflecting the pressure from the ranks below, even former right wing parliamentarians now identifying on the left. As Michael Foot put it: “ “Now some of the most silent accomplices of the previous regime had become raucous revolutionaries.” (Michael Foot, Aneurin Bevan, vol. 1, 1973).

There was a huge growth in the Labour Party’s youth section, the Labour League of Youth, with 404 branches being established across the country in 1934. In the same year, again under pressure from the rank and file, Labour’s National Executive Committee published its most radical policy document in history, For Socialism and Peace, much of which laid the foundation for Atlee’s 1945 government.

But as the mass labour movement was moving sharply to the left, ironically, the ILP were dragged to the right, as they were led by the nose by the Stalinists who now pursued a strategy of ‘Popular Frontism’. The Communist Party by 1935 had moved 180 degrees from its earlier ultra-leftism towards a position in which Stalin was seeking an accommodation on almost any terms with the capitalist West, hoping to produce ‘progressive’ governments in Europe that would align with the isolated Soviet Union.

Popular Frontism is abandoment of class politics

Stalin wagered that the open class warfare of the past few years would be a barrier to this, and in turn could encourage Western Europe to turn a blind eye to Hitler invading the Soviet Union, which, given that Stalin had purged the best elements from the Red Army, was now effectively defenceless.

Popular Frontism is the abandonment of class politics, with the independence of the labour movement expected to be subordinated to the ‘democratic status-quo’, with no explicitly socialist demands being raised, with an uncritical unity with pro-capitalist parties being pursued.

The remaining rump of the ILP joined with the Communist Party in a so-called ‘Unity’ campaign to call on the Labour Party to support a Popular Front government – all in the name of ‘national unity’ against the rise of fascism in Europe, somewhat ironic after the experience of the ‘national unity’ of the recent National Government. Indeed, the Labour leadership reminded the ILP of the 1929-31 Labour Government, and could attack them from a more left-wing position.

New Labour leader, Clement Atlee, explained to them, “The plain fact is that a socialist party cannot hope to make a success of administering the capitalist system because it does not believe in it. This is the fundamental objection to all the proposals that are put forward for the formation of a Popular Front in this country.” (Attlee, The Labour Party in Perspective, 1937)

Political developments were cut across by World War II, but Labour returned with a radical bang in the landslide victory of 1945, and all the reforms that came with it, putting the final nail into what was left of the ILP, and it disappeared from history.

Ultra-left groups abandoned Labour in the 1960s

The tragedy is that the lessons of the ILP experience have not been learnt, and every subsequent attempt to split from the Labour Party up to now has met the same fate (although usually in microcosm in scale), of sectarianism, factionalism, dogmatism and then inconsequential obscurity.

In the 1960s, various ultra-left groups abandoned the Labour Party in the excitement of the ‘New Left’ and the student movement of 1968. The three main groups that left constantly factionalised, split and ended up as the ’57 Varieties’, a few of which still litter the fringes of the labour movement today.

All the other subsequent adventures followed the same path – Militant Labour, Arthur Scargill’s Socialist Labour Party, George Galloway’s Respect, the Scottish Socialist Party and so the list goes on, all of which have crashed and burned.

Not only that. When a perfect opportunity was handed at their feet to bring their ideas and policies into the Labour Party, instead, most of these groups stood aloof from the ‘Corbyn revolution’, just as the ILP stood isolated from the dramatic turn to the left by the Labour Party in the 1930s.

Let us remind ourselves of what happened – Labour Party membership before Corbyn stood at 193,000. When Corbyn was elected leader, over 400,000 workers flooded into the party. And not just any old 400,000 – this was not a ‘one issue’ campaign, but 400,000 workers had taken a conscious political decision to enthusiastically fight for socialist policies.

Yet where were the purist ‘revolutionary’ groups? Did they hurl themselves into this swirling mass political movement to put their ideas before this receptive 600,000 strong audience? No, such was their ingrained sectarianism, that most remained in splendid isolation on the sidelines, making all sorts of rather limp excuses of why they could not get involved. Their sectarianism paralysed them.

Now, of course, with the triumph of Starmer, they smugly proclaim ‘we told you so…’ But they miss the point. Of course the defeat of Corbyn is a massive setback, and 200,000 left wing workers have subsequently left the Labour Party (current membership is just under 400,000). But where have the 200,000 gone?

Many disgruntled Labour members have left

With 200,000 lefts disgruntled with Labour on the loose, you would have thought those groups outside the Labour Party would have had a recruitment bonanza. Yet they have not expanded one iota.

The reason is that the 200,000 have gone home to lick their wounds and wait for better times. The 200,000 didn’t flood into these groups on the sidelines. The Corbyn era was the biggest political class battle of recent times, and these groups were not fighting alongside them inside the Labour Party trenches; they were ‘missing in action’ – they saw these groups then as an irrelevancy, and they still do now.

There can be no better example of why workers see such groups as an irrelevancy than the recent 2023 Rutherglen and Hamilton West by-election. Two such groups – the Scottish Socialist Party and the Trade Unionist Socialist Coalition – both stood candidates on basically the same political programme. Yet they couldn’t even agree to have one joint candidate, and instead stood against each other (not that the electorate were much troubled by these two groups, as they received only a few hundred votes between them). Workers will not take such childishness seriously.

With those disillusioned left wingers in my Labour Party, all of whom joined under Corbyn, I tell them they should not look upon the Labour Party as what it is now, but what it can become, as has been seen from the past, whether as in the 1930s and 1945, ‘Bennism’ and the growth of the Militant Tendency in the 1980s, and most recently under Corbyn.

These upsurges of the left wing in the Labour Party did not happen by accident, but in reaction to the failure of Labour’s right wing when in government – in reaction to McDonald in the 1930s, to the failure of the ‘Social Contract’ of the Callaghan government, and to the non-political ‘Third Way’ of Blair whose main legacies were PFI debts and the horrific consequences of the Iraq War. Starmer and co take note.

Activity in the Labour Party is different when in office

I also point out that activity in the Labour Party becomes a totally different beast when Labour is in government. Everything becomes concrete. Right wingers cannot, as they can when in opposition, dodge behind vacuous statements or vague policy promises.. There is no where for them to hide anymore.

The harsh truth is that any new ‘alternative’ adventure today would suffer the same fate as the ILP, and for all the same reasons. The labour movement is rallying to the Labour Party, even if it has to hold its nose at times, because it wants to get rid of this hated Tory government. They know a Labour vote is the only way to achieve this, and will not take any other ‘socialist alternative’ seriously.

So Labour Party members have to stay and fight. We need to follow the advice of Mick Lynch, General Secretary of the RMT, who recently was being goaded by the media on why he hadn’t resigned from the Labour Party.

No, he replied, he and his members weren’t going anywhere, as our job as members is to ensure the policies decided at Labour Party conference are implemented when Labour is in power, and to hold our government to account. Today, that is what we must prepare for – to be ready for tomorrow.