By John Pickard

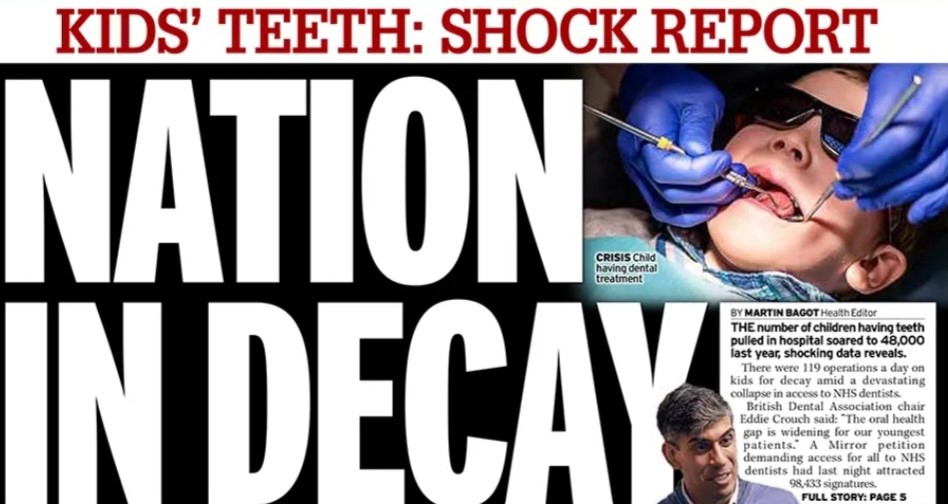

Two days ago, a TV report showed a line of hundreds of people in Bristol, queing around the block, just to register with an NHS dentist. The reporter at the scene interviewed some of those in the line and every one of them, in various words, referred to the collapse of services in this country, one even using the phrase, “Broken Britain”.

While huge amounts of wealth have been transferred from working people to the very rich, from the public sector to the private sector, there has been a catastrophic decline in investment in all of the public services on which workers depend: local authorities, Education, social services, fire services and, not least, the NHS.

There has been a similar decline in investment in national infrastructure, so that roads, railways, energy and water utilities are all, literally, crumbling. The word ‘omnishambles’ was once a good description of this Tory government, but there is a new word from the USA which might be a better fit: sharper and more pungent (literally) – “enshittification”.

The word was coined particulary in relation to social media, as an article in the Financial Times pointed out. The author, Cory Doctorow, first used the expression to describe the decay of social media platforms and in some circles the word took off. The American Dialect Society made it Word of the Year for 2023. “We’re all living through a great enshittening,” Doctorow writes, “in which the services that matter to us, that we rely on, are turning into great piles of shit. It’s frustrating. It’s demoralising. It’s even terrifying.”

Facebook and mutual ‘hostage-taking’

Doctorow deals in his FT article particularly with social media, describing the three stages of their decay. “…first, platforms are good to their users. Then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers. Finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves. Then, there is a fourth stage: they die.”

Doctorow then proceeds to describe in detail the example of Facebook, once seen as a benign and useful tool. It was more flexible than MySpace, so it quickly picking up the latter’s users, and hundreds of millions more as well.

When so many friends, families and associates are signed up to the same platform, as a user, there is a ‘network’ effect, making it difficult to abandon. It has become ‘essential’ and switching elsewhere comes with social and personal costs that most people are not prepared to meet. In this phase, as Doctorow puts it, it is like “mutual hostage-taking”, as everyone is glued to the platform.

It was at this point that phase two kicked in, as Facebook decided to sell metadata to businesses, fine-tuning their (paid) adverts to groups and individuals based on the information – ‘likes’, ‘dislikes’, ‘follows’, etc – from billions of people. Facebook guarantees to businesses that their ads will be seen by real people. “And so,” Doctorow writes, “advertisers and publishers became stuck to the platform, too. Users, advertisers, publishers — everyone was locked in”.

The third phase involves Facebook diluting the content that we want to follow – to a “homeopathic dose” – and adding a lot more adverts and bits and pieces we don’t want to see. We’ve all experienced that. Along with higher fees for advertisers, it means that the shareholders of Facebook are into the real plundering period, milking the attachment of billions to the platform, and taking billions of dollars, but from increasingly frustrated users and advertisers.

Too big to fail, too big to jail

Doctorow’s article is extremely long and convoluted, and not recommended, even without the FT paywall. Worst of all, it amounts to an extended appeal for more regulation and enforced competition between different tech companies and social media platforms.

It is also a pity that he focuses almost entirely on social media, although buried in the text he makes some pertinent points about the process of monopolisation that has gone on untrammelled for decades across all industries and sectors of the economy. “Most of our global economy is dominated by five or fewer global companies”, he argues. It is this consolidation and cartel dominance that puts big companies in a position where they don’t need to “care” or offer any public accountability.

These giant companies are “too big to fail” and their leaders “too big to jail.” Unfortunately, Doctorow does not develop this argument further, nor the fact that the size of these monopolies means that they can have legions of politicians, legislators and civil servants in their pockets.

We know these giant companies don’t care, because they don’t ‘need’ to. Think Post Office scandal. Think privatised water companies, pouring billions of tonnes of raw sewage. Think big banks ‘fined’ for money laundering. Thnk tax-dodging on an industrial scale. Think energy companies oblivious to climate change. And so on.

In relation to tech companies, Doctorow explains how the likes of Facebook and Google have been “unscathed by European privacy law”, basically because they “pretend” to be headquartered in Ireland, or Malta or Luxemburg or another tax and regulatory haven. His article goes on at great length – “the longest ever rant in the Financial Times” as one commenter wrote underneath – but nowhere is there a solution advanced, beyond a utopian attachment to more competition and regulation.

For a socialist, the increased monopolisation of companies, including big tech, is a further argument for their public ownership and democratic management. The idea of social media platforms, for example, is not intrinsically bad. Indeed they can be an extremely useful personal and social tool. But the private ownership and exploitation of social media makes it toxic.

Social media is useful only up to a point and it has serious flaws

Social media platforms may be all well used by the labour movement and that is understandable. Left Horizons uses some platforms to ‘signpost’ articles on the website, but for little else. As a means of promoting ‘discussion’ or ‘political education’, they are worse than useless: each one an endless feed, the contents of which are overwhelmingly shallow, trivial and above all, transient.

The goal of the Left Horizons website is the creation of a Marxist current of opinion within the labour movement. But there can be no illusions in social media as being anything more than a useful implement and a secondary one at that. A real movement will be built by face-to-face contacts, discussions, and cooperative political activity, in real physical surroundings, building experience, trust and comradeship.

Private corporations are only one side of the issue because for most working families the services on which they depend are also those paid for by national and local government. These, too, have decline from lack of investment, to the point where there is universal scepticism about their usefulness.

Social media use and government cuts are coming together in the USA, where government money – or the lack of it – is now threatening the subsidises for internet connection, upon which 23m low-income households depend.

As for “enshittification”, it is doubtful that the word will catch on very much; it is too much of a mouthful, if you can pardon the gross imagery. But in a very serious way, the destruction of public services, the NHS, infrastructure, right down to the plague of potholes on our roads, will all add to the frustrations of millions of workers and the perception that nothing is working any more.

It is creating a crescendo of mood music that is saying that the Tories are finished, and a guarantee that they will be smashed in the next election. And the sooner the better.