By Maureen Wade

Chair, Birmingham UNISON Retired Members Section

March 8 marks International Working Women’s Day, and as it is the 40th anniversary of the Miners’ Strike 1984-85, many events this year will commemorate the role of the women in the mining communities during that year-long struggle.

It should always be remembered that International Women’s Day came from the labour movement. The very first such event was called by the Socialist Party of America in New York in 1909.

This inspired the women delegates to the International Socialist Women’s Conference in Europe, which was running alongside the meeting of the Second International, at that time the international grouping of the mass workers’ parties. The German delegation, led by Clara Zetkin, called for a special day each year for women to hold mass protests to demand suffrage and equal rights.

First International Working Women’s Day

The first such day in 1911 resulted in mass protests across Europe, with 300 demonstrations in Austro-Hungary alone, as well as huge marches in Germany, Denmark and Switzerland – incredibly for the latter, women were still fighting for the right to vote as late as 1971, when it was finally granted.

After the success of the Russian Revolution, leading Bolshevik, Alexandra Kollontai, served as the People’s Commissar for Welfare in Lenin‘s government in 1917–1918, becoming the first woman to be a cabinet minister, and also the world’s first woman ambassador. She led the campaign for International Women’s Day to be formally recognised and held every year on 8 March, which has been marked ever since.

As votes for women began to be won, support for International Women’s Day began to wane, until its revival by the feminist movement of the late 1960s, as women took up the struggle for equal pay, equal rights, the right to choose, and against violence against women.

As feminist theory developed, while important victories were gained, the original class element of the movement began to be overshadowed by sometimes even separatist ideas. With International Women’s Day becoming adopted by the United Nations in 1977, it got increasingly institutionalised, and used as a cover by capitalist and despotic governments to pretend to promote women’s rights – similar to the ‘green washing’ over climate change that goes on today.

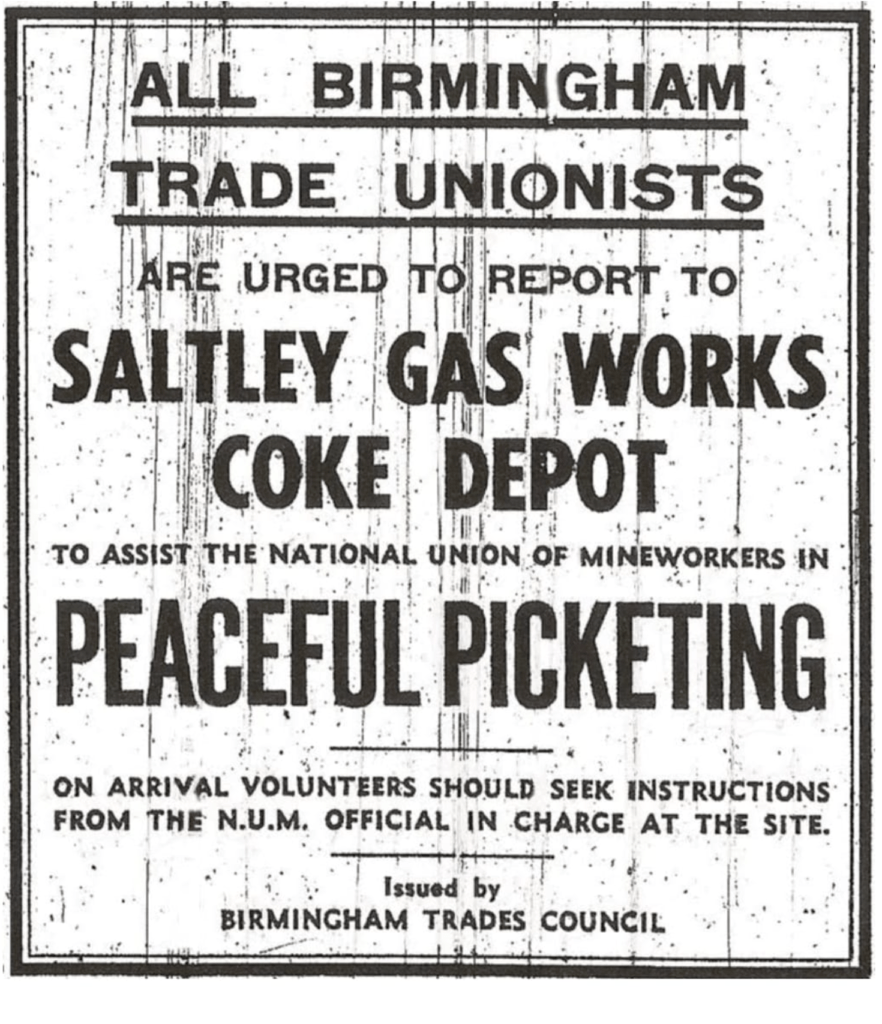

The miners’ strike 1984-85 brought that class element back into the movement. I am not from a mining family, but grew up in the Nechells back-to-backs in the shadow (and smell!) of Saltley gas works and coke plant in Birmingham. As a young girl, I remember the 1972 miners’ strike well. My dad was an engineering union shop steward in the AUEW, and joined the famous call with thousands of other factory workers to support the miners who were picketing the Saltley plant. I remember his excitement, rushing back home shouting “We’ve shut the gates! We’ve shut the gates!”.

Huge march of miners’ wives through London

But that strike, it has to be said, was very much a male-dominated affair. The 1984 strike was different. The women got involved from the start. Within a few weeks of the strike being called, Women Against Pit Closures was formed. By May 5,000 women from mining villages in South Yorkshire held a mass rally in Barnsley, and by the summer, the movement could muster 23,000 women from the pits to march though London.

I found an article in the Guardian from 10 years ago, which succinctly summed up the impact this movement had:

“It propelled miners’ wives, sisters and daughters into the heart of the epic struggle against the Thatcher government, challenged miners and other trade unionists’ assumptions about gender roles, and galvanised a feminist movement that had been dominated by middle class, educated women. The ideas of feminism – political, economic, social equality and independence – channelled back into the mining communities” (Guardian, 7 April 2014).

I saw that process for myself. By 1984, I was married and living in East London, and we were regularly putting up striking miners as they came to London to raise money and address solidarity meetings.

The pit villages were very much ‘closed communities’ in that all the men worked down the pit, and the women brought up the children and ran the home, perhaps with a part-time job, too. For many miners, the cosmopolitan ways of London were quite a shock.

One of the first group of miners who stayed with us were six men from Ashington in Northumberland. I remember their look of puzzlement when they first arrived, as I engaged them in political discussion…while my husband was in the kitchen cooking our meals!

Equally, they had little experience of multi-cultural communities, and casually used racist terms. We didn’t lecture them – we said to them, when you go out tomorrow around East Ham, knocking on doors to raise money, just see who gives you money. Sure enough, they returned the next evening full of praise for the Asian community that had showered them with money, food, treats and drinks. These miners were meant to return home on the Friday, but stayed over an extra day, to make a point of attending a mass Anti-Apartheid demonstration being held on that day.

“We’re like pit ponies, seeing the sunshine for the first time.”

Meanwhile, when the miners’ wives came to our ‘womens’ groups’ in London, they ‘proletarianised’ them, and rather than sitting in an angst-ridden feminist bubble,we set about the task of getting out there to rattle the buckets to raise funds, taking us into the community and labour movement. Indeed, groups like the Women’s Peace Camp at Greenham Common learnt a thing or two from the miners’ wives about tactics when in confrontation with the police.

These experiences did raise the consciousness of many miners – as a striking Nottinghamshire miner staying with us remarked: “We’re like pit ponies that have been allowed out into the sunshine for the first time.” But equally, the role of the women became a necessity as mining communities had to fight total war and the Thatcher government threw every weapon in the state machine at them.

It became important for the wives and families to join the picket lines, as a government tactic was to get the police to paint a line around the pit gate, and any striking miner who stepped over it would be arrested and then sacked from his job for ‘trespassing on National Coal Board property’. But they couldn’t use this tactic on the women, because they were not employed by the NCB.

Involvement in mass picketing hardened many of the women, particularly when police began invading the pit villages in force to terrorise the communities back to work. Many villages began to resemble Northern Ireland in the worst days of the Troubles.

A miner’s wife from Cortonwood described her experience of the first mass pickets, where the Met Police were brought up from London, and then ran riot through the village:

“I’m not saying I agree with throwing bricks, but if you see men running amok with three foot batons! I’d never thrown a stone in my life… First morning of the mass picket I never threw a stone, but second morning I went down with a bloody bag full… I put a flask and towel on top and said I was taking some drinks down, and underneath it was full of bricks I’d picked up from my own garden.

“you had nothing to fight back with. They had everything”

“What could you do? Hundreds (of police) after you and it didn’t matter who you were, you got it off them! I never threw them again but that morning it was frustration – it was my village they were in; it was our place and they had no business being there and doing that… you had nothing to fight them back with, they had everything, you had nothing” (10 Years On And Still Laughing, D.Fitzpatrick, C Nelson, M Cadwallader, E Armitage, 1994).

One of the cruellest measures used by Thatcher was to cut benefits to the miners’ families, in an attempt to starve them back to work. The first cut was £15 a week, increased to a £16 cut (the equivalent today of around £65) in the winter of 1984-85 – the government claimed the deduction was because miners were receiving strike pay from the NUM, which they weren’t.

This caused massive hardship, and the mining communities had to collectivise to survive. The women ran soup kitchens and made up ‘ration parcels’ with food and money donations from the wider labour movement. The main role of their children meanwhile was to scavenge for any fuel to keep the fires burning in their homes.

This total involvement meant a new relationship within mining families. Brenda Procter, a miner’s wife in Stoke-on-Trent said it was during the strike that she and her husband Ken began sharing childcare and domestic chores: “He’d been picketing, and would come home to look after the kids while I went to meetings. He was quite happy doing that. Miners had a new respect for women” (Guardian, 7 April 2014).

At this year’s events to celebrate International Women’s Day, we should remember the role played by women in the miners’ strike. When we look around the world, from the USA to Iran or Afghanistan, it seems women’s rights are returning to the dark ages. We are going to need the grit and determination of the women from the pit villages of 1984-85 to push back the tide.