By Hilary Barker

Today, since the election the hard right candidate, Javier Milei, the working class of Argentina is facing huge attacks on their living standards and on the democratic rights they established over many years. Women’s rights are under attack, as are welfare rights but across the board, workers are responding. This first part of a two-part article by Hilary Barker, looking at the historic background to the election of Milei in December last year.

…………………………………………………………….

Growing up in the 1950s, with continuined rationing, Argentina simply meant corned beef to me, and little else. It wasn’t until the 1980s that I became aware of its people and the horrors committed upon them by oppressive military dictatorships between 1976 and 1979. Almost 30,000 Argentinians “disappeared” during these years.

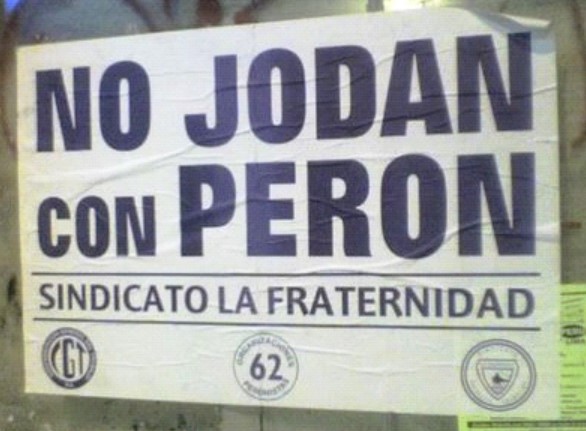

During the early postwar years, the president, Juan Peron, carried out significant reforms that benefitted the working class. He invested in public works, expanded social welfare, granted rights to trade unions, which grew enourmously, and extended the franchise to women. He even forced employers to improved working conditions and wages. Peron was no socialist and his methods were undemocratic and dictatorial, but ‘Peronism’ is still remembered by workers as a movement of reforms.

Peron was overthrown in a coup in 1955, having been president for nine years, and he was followed by a succession of short-lived military and civilian governments. It was not until 1967 that Peronists were permitted to participate in Argentina’s political life, resulting in them going on to win the next election and to the return of Peron.

Improved living conditions

Alicia Portnoy, in her book, The Little School, describes how as a teenager in 1967 she learned that it was Peronism that had given power to workers by organising them into strong unions, improving living conditions through fair wages, retirement plans, holidays, a good public health system and women’s right to vote.

She writes ”by 1975, Peron had died, and Isobel, his third wife and vice-President was left in charge…she handed over control of the repressive apparatus to the military”. They quickly began to attack the youth movement as a possible threat to the military leaders, and paramilitary groups were formed to kidnap and kill political activists with the help of the police. This prompted The Revolutionary people’s Party (ERP) and the Montoneros to target members of the Armed Forces and big factory owners who were ignoring workers.

But the policy of so-called ‘urban guerillaism’ which was followed by these groups on the ultra-left, was a fancy dressing up of individual terrorism and it failed utterly to promote a widespread movement of workers. Worse still, it gave the state the opportunity and pretext to clamp down savagely on the left.

What followed was horrific, because anyone on the left, particularly young people, were kidnapped, tortured and killed. More than 30,000 were killed in a one-sided civil war. Babies born in prison were taken and given to couples of the right political persuasion with no paper trails to say who their parents were. It is only since the ability to “find” people through DNA that some of these babies, the lucky ones, have been able to trace their biological parents.

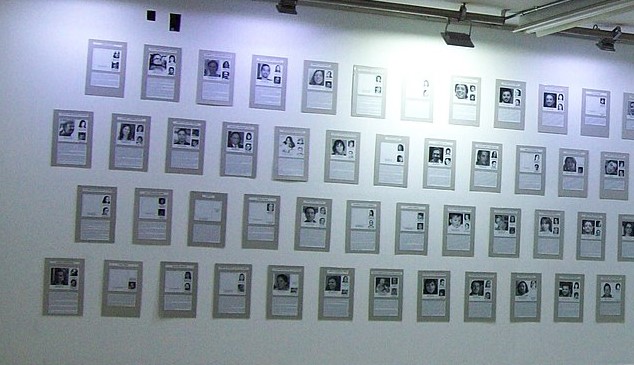

Children of the disappeared

In 1984, the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons, (in Spanish: Comisión Nacional sobre la Desaparición de Personas or CONADEP) published a report. By this time, the Asociación Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo (Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo or Abuelas), was already active and had record of 172 children who had either disappeared, together with their parents, or were born at the numerous concentration camps and had not been returned to their wider families.

The Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo now believe that up to 500 grandchildren were stolen, but only 102 are believed to have been located. On October 6, 1978, 25-year-old Patricia Julia Roisinblit de Perez, who was active in the Montoneros, was kidnapped, along with her husband, 24-year-old José Martínas Pérez Rojo, and their child was born in detention.

Many years later, on 13 April 2000, the child’s grandmother, Rosa Roisinblit, received a tip-off that the birth certificate of the baby grandson, was falsified and that he had been given to an Air Force civil agent and his wife. Following the anonymous phone call, the child, now Rodolfo Fernando and grown up, was located and agreed to a DNA blood test, confirming his true identity. This man, the grandson of Rosa Roisinblit, was first known newborn of missing children returned to his family through the work of the Grandmothers.

The case of Maria Eugenia Sampallo (born some time in 1978) also received considerable attention, as Sampallo sued the couple who adopted her illegally as a baby after her parents disappeared, both Montoneros. Her grandmother spent 24 years looking for her. The case was filed in 2001 after DNA tests indicated that Osvaldo Rivas and Maria Cristina Gomez were not her biological parents. Along with army Captain Enrique Berthier, who furnished the couple with the baby, they were sentenced respectively to 8, 7 and 10 years in prison for kidnapping.

Military government defeated in the Malvinas

This was the same military government, now under General Galtieri, that was defeated by the British in the Malvinas, known in Britain as the Falkland Islands. That military defeat, and the appalling loss of life of Argentine soldiers and sailors – 650 were killed, in a war lasting two and a half months – led to a big movement of opposition against the military government, which collapsed, and there was a return to civilian rule in 1983.

The government of Raúl Alfonsín worked to end the human rights abuses that had characterized the former regimes. Hyperinflation, however, led to public riots and Alfonsín’s party’s was defeated at elections in 1989 by Peronist, Carlos Menem, who instituted laissez-faire economic policies and so also quickly became unpopular.

The old ‘Peronism’ might have been associated with reforms, but without a socialist policy and perspective – that would have meant taking over the banks, land and industries – the new so-called ‘left’ leaders inevitably allowed a ruined and corrupt Argentine capitalism to dictate government policy.

In 1999, Fernando de la Rúa of the Alliance coalition was elected president, but his administration struggled with rising unemployment, heavy foreign debt, and government corruption; he was forced to resign later that year, amid anti-government protests. With a succession of interim presidents, Argentina experienced one of its worst economic collapses, at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Néstor Kirchner won the 2003 presidential elections, on a promise to improve living standards and for a time there was some stabilisation in the economy.

Four years later his wife, Cristina, became the country’s first elected female president. She described herself as a ‘Peronist’ and a ‘progressive’, and although she based herself on capitalism, she attempted to continue the Peronist tradition of reforms in the workers’ intersts. She renationalised private pension funds and fired the president of the National Bank. She imposed import regulations, to encourage local production and exports, and faced with a rising international debt, initiated negotiations to pay off Argentina’s debt.

Kirchner’s reforms extremely popular

In 2012, she even renationalized YPF, an oil firm, with the result that there was a reaction from foreign bond and debt-holders, particularly in the US. A new cash transfer program was launched, called (AUH), which provided financial assistance to low-income families, like child benefits, enabling them to send their children to school and have vaccinations.

During her presidency, same-sex marriage was legalized, and a new law was passed that allowed name and sex change in official documents for transgender people, even if they had not undergone sex reassignment surgery.

In September 2011 Kirchner addressed the United Nations, supporting the Palestinian request to be seated in the General Assembly, and threatening to cancel flights from Chile to the Malvinas/Falkland Islands in order to advance Argentine claims of sovereignty over the Islands. Kirchner’s radicalism paid off in terms of her popularity and in 2011, (with some sympathy support after the sudden death of her husband and former president) won the election with 54.1% of the vote.

Even by 2015, when she left office, she had approval ratings above 50%. Instead of standing for another term herself, she supported the then Peronist candidate Daniel Scioli. But by then, the gloss was rubbing off Peronism as living standards were being eroded by inflation. ‘Half’ a revolution inevitably allows to the capitalist class and the right to sabotage the economy and to reorganise and hit back. So, in the 2015 election, conservative Maurice Makri elected.

Despite promises he had made for ‘change’ – he would not have been elected otherwise – Makri cut subsidies on which working families depended, but did not cut taxes. Caught within the limitations of the Argentine capitalist system, Makri’s government headed for bankruptcy and had to be bailed out by the IMF to the tune of $50bn. In return for the loan, however, the Argentine government was obliged to cut public spending, local government services and other elements of the ‘social wage’ upon which workers relied.

Failure of the left paved the way for reaction in December 2023

In 2019, the Centre-Left Peronist Alberto Fernandez was elected President, after defeating the incumbent Makri in the general election. His vice president was Cristina Kirchner with whom he regularly consulted. Then on 14 November 2021, the centre-left coalition of Argentina’s ruling Peronist party, (Front for Everyone), lost its majority in Congress, for the first time in almost 40 years, in midterm elections.

The election victory of the center-right coalition, (Together for Change), meant a tough final two years in office for President Alberto Fernandez. Losing control of the Senate made it difficult for him to make key appointments, including to the judiciary. It also forced him to negotiate with the opposition with every initiative he sent to the legislature.

This paved the way for the election of the right-wing candidate last year. The post-war history of Argentina was dominated by constant economic crisis in a corrupt and bankrupt system. Whenever left governments attempted reforms, they were inevitably sabotaged and undermined, with the result that living standards fell and workers became disillusioned. It was the constant failure of the left to provide a way out of the impasse of Argentine capitalism that paved the way for disappointment and disenchantment, and eventually the election of the most right-wing president for decades, Javier Milei.

Part two of this article will deal with Argentina under Milei

[Top and second picture inset: Hall of memory in homage to the neonates kidnapped during the civic-military dictatorship that governed Argentina from 1976 to 1983, at the National Technological University (UTN) Regional Faculty of Avellaneda, Villa Dominico, Argentina. All pictures from Wikimedia Commons]