This is the second part (of three) of the Workshop Talks section of James Connolly’s 1909 booklet Socialism Made Easy. Part one, dealing with internationalism (and charity) is here, where you can also find an introduction and a short biography of Connolly. Part Three (here) deals with issues of religion and “national freedom”.

In this second, longer, part, he deals with welfare; bosses and workers; profit; the confiscation of private businesses; and “practical” reforms vs revolutionary change.

It is stirring, inspiring and witty stuff. These days we might say that Connolly is on fire!

Some things have changed over the last 112 years, of course, but it’s remarkable how relevant the arguments still are – and becoming more so! He does address, throughout, working men, specifically, and reflects some other attitudes of the time. We have only edited for minor punctuation and a point of clarification.

*****

But the Socialist proposals, they say, would destroy the individual character of the worker. He would lean on the community, instead of upon his own efforts.

Yes: Giving evidence before the Old Age Pensions’ Committee in England, Sir John Dorrington, M.P., expressed the belief that the “provision of Old Age Pensions by the State, for instance, would do more harm than good. It was an objectionable principle, and would lead to improvidence.”

There now! You will always observe that it is some member of what an Irish revolutionist called “the canting, fed classes,” who is anxious that nothing should be done by the State to give the working-class habits of “improvidence,” or to do us any “harm.” Dear, kind souls!

To do them justice, they are most consistent. For both in public and in private their efforts are the most whole-heartedly bent in the same direction, viz., to prevent improvidence – ON OUR PART.

They lower our wages – to prevent improvidence; they increase our rents – to prevent improvidence; they periodically suspend us from our employment – to prevent improvidence; and as soon as we are worn out in their service, they send us to a semi-convict establishment, known as the Workhouse, where we are scientifically starved to death – to prevent improvidence.

Old Age Pensions might do us harm. Ah, yes! And yet, come to think of it, I know quite a number of people who draw Old Age Pensions and it doesn’t do them a bit of harm. Strange, isn’t it?

Then all the Royal Families have pensions, and they don’t seem to do them any harm; royal babies, in fact, begin to draw pensions and milk from a bottle at the same time.

Afterwards, they drop the milk, but they never drop the pensions – nor the bottle.

Then all our judges get pensions, and are not corrupted thereby – at least not more than usual. In fact, all well-paid officials in government or municipal service get pensions, and there are no fears expressed that the receipt of the same may do them harm.

But the underpaid, overworked wage-slave. To give him a pension would ruin his moral fibre, weaken his stamina, debase his manhood, sap his integrity, corrupt his morals, check his prudence, emasculate his character, lower his aspirations, vitiate his resolves, destroy his self-reliance, annihilate his rectitude, corrode his virility – and – and – other things.

Let us be practical. We want something pr-r-ractical.

Always the cry of hum-drum mediocrity, afraid to face the stern necessity for uncompromising action. That saying has done more yeoman service in the cause of oppression than all its avowed supporters.

The average man dislikes to be thought unpractical, and so, while frequently loathing the principles or distrusting the leaders of a particular political party he is associated with, declines to leave them, in the hope that their very lack of earnestness may be more fruitful of practical results than the honest outspokenness of the party in whose principles he does believe.

In the phraseology of politics, a party too indifferent to the sorrow and sufferings of humanity to raise its voice in protest is a moderate, practical party; whilst a party totally indifferent to the personality of leaders, or questions of leadership, but hot to enthusiasm on every question affecting the well-being of the toiling masses, is an extreme, a dangerous party.

Yet, although it may seem a paradox to say so, there is no party so incapable of achieving practical results as an orthodox political party; and there is no party so certain of placing moderate reforms to its credit as an extreme – a revolutionary – party.

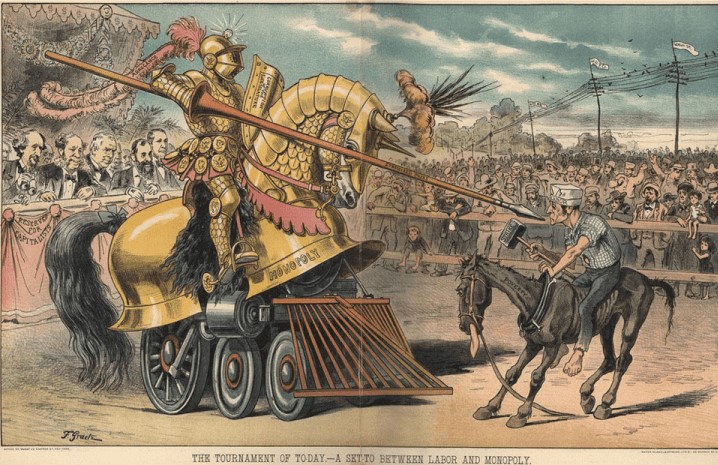

The possessing classes will, and do, laugh to scorn every scheme for the amelioration of the workers so long as those responsible for the initiation of the scheme admit as justifiable the “rights of property”; but when the public attention is directed towards questioning the justifiable nature of those “rights” in themselves, then the master class, alarmed for the safety of their booty, yield reform after reform – in order to prevent revolution.

Moral – Don’t be “practical” in politics. To be practical in that sense means that you have schooled yourself to think along the lines, and in the grooves, those who rob you would desire you to think.

In any case, it is time we got rid of all the cant about “politics” and “constitutional agitation” in general. For there is really no meaning whatever in those phrases.

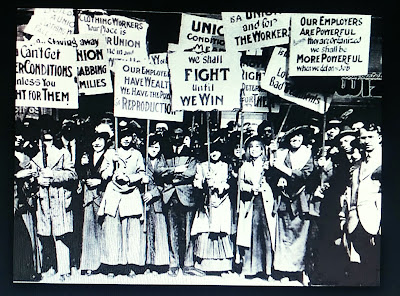

Every public question is a political question. The men who tell us that Labour questions, for instance, have nothing to do with politics, understand neither the one nor the other. The Labour Question cannot be settled except by measures which necessitate a revision of the whole system of society, which, of course, implies political warfare to secure the power to effect such revision.

If by politics we understand the fight between the outs and the ins, or the contest for party leadership, then Labour is rightly supremely indifferent to such politics, but to the politics which centre round the question of property and the administration thereof, Labour is not, cannot be, indifferent.

To effect its emancipation, Labour must reorganise society on the basis of labour; this cannot be done while the forces of the government are in the hands of the rich, therefore the governing power must be wrested from the hands of the rich, peacefully, if possible, forcibly if necessary.

In the phraseology of the master class and its pressmen, the trade unionist who is not a socialist is more practical than he who is, and the worker who is neither one nor the other but can resign himself to the state of slavery in which he was born, is the most practical of all men.

The heroes and martyrs who in the past gave up their lives for the liberty of the race were not practical, but they were heroes all the same.

The slavish multitude, who refused to second their efforts from a craven fear lest their skins might suffer, were practical, but they were soulless serfs, nevertheless.

Revolution is never practical – until the hour of the Revolution strikes. Then it alone is practical, and all the efforts of the conservatives and compromisers become the most futile and visionary of human imaginings.

For that hour, let us work, think, and hope; for that hour let us pawn our present ease in hopes of a glorious redemption; for that hour let us prepare the hosts of Labour with intelligence sufficient to laugh at the nostrums dubbed practical by our slave-lords, practical for the perpetuation of our slavery; for that supreme crisis of human history let us watch, like sentinels, with weapons ever ready, remembering always that there can be no dignity in Labour until Labour knows no master.

Would you confiscate the property of the capitalist class and rob men of that which they have, perhaps, worked a whole life-time to accumulate?

Yes sir, and certainly not.

We would certainly confiscate the property of the capitalist class, but we do not propose to rob anyone. On the contrary, we propose to establish honesty once and forever as the basis of our social relations. The Socialist movement is indeed worthy to be entitled The Great Anti-Theft Movement of the Twentieth Century.

You see, confiscation is one great certainty of the future for every business man outside the trust. It lies with him to say if it will be confiscation by the Trust in the interest of the Trust, or confiscation by Socialism in the interest of All.

If he resolves to continue to support the capitalist order of society, he will surely have his property confiscated. After having, as you say, “worked for a whole life-time to accumulate” a fortune, to establish a business on what he imagined would be a sound foundation, on some fine day the Trust will enter into competition with him, will invade his market, use their enormous capital to undersell him at ruinous prices, take his customers away from him, ruin his business, and finally drive him into bankruptcy, and perhaps to end his days as a pauper.

That is capitalist confiscation! It is going on all around us, and every time the business man who is not a Trust Magnate votes for capitalism, he is working to prepare that fate for himself.

On the other hand, if he works for Socialism, it will also confiscate his property. But it will only do so in order to acquire the industrial equipment necessary to establish a system of society in which the whole human race will be secured against the fear of want for all time, a system in which all men and women will be joint heirs and owners of all the intellectual and material conquests made possible by associated effort.

Socialism will confiscate the property of the capitalist and in return will secure the individual against poverty and oppression; it, in return for so confiscating, will assure to all men and women a free, happy and unanxious human life. And that is more than capitalism can assure anyone to-day.

So, you see, the average capitalist has to choose between two kinds of confiscation. One or the other he must certainly endure. Confiscation by the Trust and consequent bankruptcy, poverty and perhaps pauperism in his old age, or

Confiscation by Socialism and consequently security, plenty and a Care-Free Life to him and his to the remotest generation.

Which will it be?

But it is their property. Why should Socialists confiscate it?

Their property, eh? Let us see: Here is a cutting from the New York World, giving a synopsis of the Annual Report of the Coats Thread Company of Pawtucket, Rhode Island, for 1907. Now, let us examine it, and bear in mind that this company is the basis of the Thread Trust, with branches in Paisley, Scotland, and on the continent of Europe.

Also bear in mind that it is not a “horrible example,” but simply a normal type of a normally conducted industry, and therefore what applies to it will apply in a greater or less degree to all the others.

This report gives the dividend for the year at 20 per cent per annum. Twenty per cent dividend means 20 cents on the dollar profit. Now, what is profit?

According to Socialists, profit only exists when all other items of production are paid for. The workers by their labour must create enough wealth to pay for certain items before profit appears. They must pay for the cost of the raw material, the wear and tear of machinery, buildings etc. (the depreciation of capital), the wages of superintendence, their own wages, and a certain amount to be left aside as a reserve fund to meet all possible contingencies. After, and only after, all these items have been paid for by their labour, all that is left is profit.

With this company, the profit amounted to 20 cents on every dollar invested.

What does this mean? It means that in the course of five years – five times 20 cents equals one dollar – the workers in the industry had created enough profit to buy the whole industry from its present owners. It means that after paying all the expenses of the factory, including their own wages, they created enough profit to buy the whole building, from the roof to the basement, all the offices and agencies, and everything in the shape of capital. All this in five years.

And after they had so bought it from the capitalists, it still belonged to the capitalists.

It means that if a capitalist had invested $1,000 in that industry, in the course of five years he would draw out a thousand dollars, and still have a thousand dollars lying there untouched; in the course of ten years, he would draw out two thousand dollars; in fifteen years, he would draw three thousand dollars. And still his first thousand dollars would be as virgin as ever.

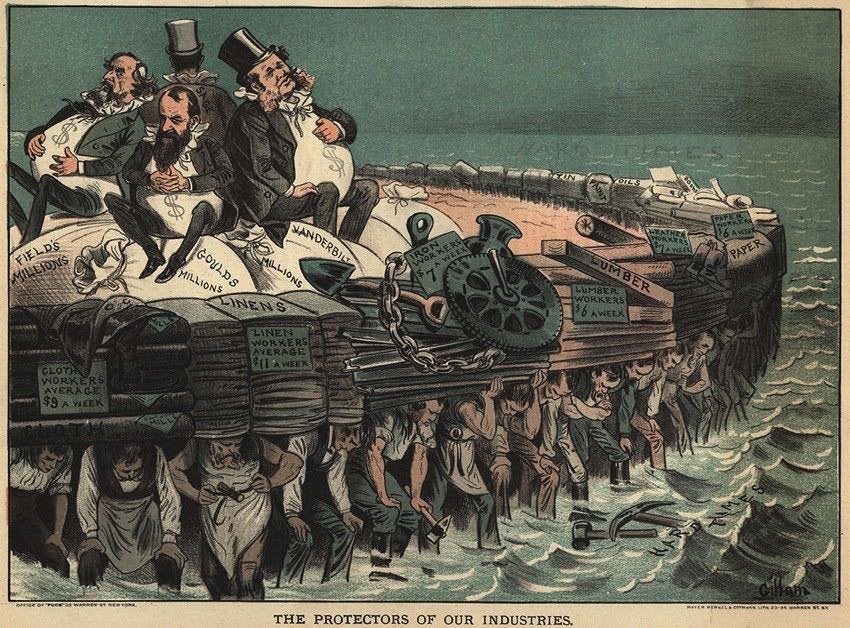

You understand that this has been going on ever since the capitalist system came into being; all the capital in the world has been paid for by the working class over and over again, and we are still creating it, and recreating it. And the oftener we buy it, the less it belongs to us.

The capital of the master class is not their property; it is the unpaid labour of the working class – “the hire of the labourer kept back by fraud.”

Oh, the capitalist has his anxieties, too. And the worker has often a good time.

Sure: Say, where were you for your holidays?

Were you tempted to go abroad? Did you visit Europe? Did you riot, in all the abandonment of a wage slave let loose, among the pleasure haunts of the world?

Perhaps you rambled among the vine clad hills of sunny France, and visited the spots hallowed by the hand of that country’s glorious history.

Perhaps you sailed up the castellated Rhine, toasted the eyes of bewitching frauleins in frothy German beer, explored the recesses of the legend-haunted Hartz mountains, and established a nodding acquaintance with the Spirit of the Brocken.

Perhaps you traversed the lakes and fjords of Norway, sat down in awe before the neglected magnificence of the Alhambra, had a cup of coffee with Menelik of Abyssinia, smelt, afar off, the odors of the streets of Morocco, climbed the Pyramids of Egypt, shared the hospitable tent of the Bedouin, visited Cyprus, looked in at Constantinople, ogled the dark-eyed beauties of Circassia, rubbed up against the Cossack in his Ural Mountains, or…

Perhaps you lay in bed all day in order to save a meal, and listened to your wife wondering how she could make ends meet with a day’s pay short in the weekly wages.

And whilst you thus squandered your substance in riotous living, did you not ever stop to think of your master – your poor, dear, overworked, tired master?

Did you ever stop to reflect upon the pitiable condition of that individual who so kindly provides you with employment, and does no useful work himself in order that you may get plenty of it?

When you consider how hard a task it was for you to decide in what manner you should spend your Holiday; where you should go for that ONE DAY, then you must perceive how hard it is for your masters to find a way in which to spend the practically perpetual holiday which you force upon them by your love for work.

Ah, yes, that large section of our masters who have realised that ideal of complete idleness after which our masters strive, those men who do not work, never did work, and with the help of God – and the ignorance of the people – never intend to work, how terrible must be their lot in life!

We, who toil from early morn till late at night, from January till December, from childhood to old age, have no care or trouble or mental anxiety to cross our mind – except the landlord, the fear of loss of employment, the danger of sickness, the lack of common necessities (to say nothing of luxuries), for our children, the insolence of our superiors, the unhealthy condition of our homes, the exhausting nature of our toil, the lack of all opportunities of mental cultivation, and the ever-present question whether we shall shuffle off this mortal coil in a miserable garret, be killed by hard work, or die in the Poorhouse.

With these trifling exceptions, we have nothing to bother us; but the boss, ah, the poor, poor boss!

He has everything to bother him. Whilst we are amusing ourselves in the hold of a ship shoveling coal, swinging a hammer in front of a forge, toiling up a ladder with bricks, stitching until our eyes go dim at the board, gaily riding up and down for twelve hours per day, seven days per week, on a trolley car, riding around the city in all weathers with teams [of horses – LH] or swinging by the skin of our teeth on the iron framework of a skyscraper, standing at our ease OUTSIDE the printing office door listening to the musical click of the linotype as it performs the work we used to do INSIDE, telling each other comfortable stories about the new machinery which takes our place as carpenters, harness-makers, tinplate-workers, labourers, etc., in short, whilst we are enjoying ourselves, free from all mental worry.

Our unselfish, tired-out bosses are sitting at home, with their feet on the table, softly patting the bottom button of their vests.

Working with their brains.

Poor bosses! Mighty brains!

Without our toil, they would never get the education necessary to develop their brains; if we were not defrauded by their class of the fruits of our toil, we could provide for education enough to develop the mental powers of all, and so deprive the ruling class of the last vestige of an excuse for clinging to mastership, viz., their assumed intellectual superiority.

I say “assumed,” because the greater part of the brainwork of industry to-day is performed by men from the ranks of the workers, paid high salaries in proportion as they develop expertness as slave-drivers.

As education spreads among the people, the workers will want to enjoy life more; they will assert their right to the full fruits of their labour, and by that act of self-assertion lay the foundation of that Socialist Republic in which labour will be so easy, and the reward so great, that life will seem a perpetual holiday.