By Sue Denham

Audrey White’s dispute with Lady at Lord John Liverpool, 1983

Forty years ago, a clothing shop manager in Liverpool, Audrey White, took a stand against the sexual harassment of the female staff she managed by a male manager. When she complained to her manager she got the sack, triggering a dispute that lasted months.

Against all expectations, Audrey won that dispute, and it led eventually to a change in the law to protect women workers from this kind of abuse, and also a recognition by unions that they must take sexual harassment seriously, and that this form of coercion and bullying must be combatted However, it was not until 2005, more than 20 years later, with the passing of an amendment to the Sex Discrimination Act 1975, that a legal definition of “harassment” was set out in law.

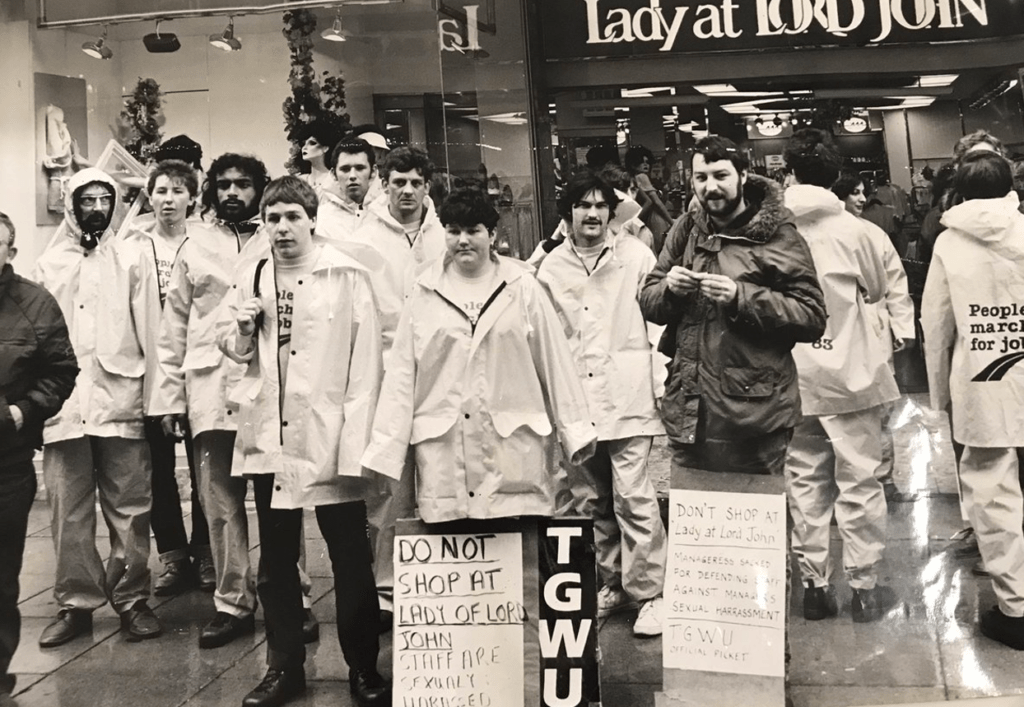

The owners of Lady at Lord John, Werff, refused to recognise or negotiate with the TGWU (now UNITE), so Audrey White and her family and supporters decided to organise a picket of the shop in Liverpool and urged the public to boycott the shop. Picketing proved to be a good tactic, as the company was gearing up for a launch of the newly refurbished interior and did not reckon on White and her supporters being there all day, every day for five weeks, from late April 1983.

Overcoming a large and wealthy company

Aided initially only by her friends, family and the trade union movement, Audrey was joined by many sympathisers and eventually managed to overcome a large and wealthy company, backed as it was by the state using the Thatcher government’s anti-trade union laws. Her opponents did not even scruple at taking out an injunction against Audrey, her father and brother and the union for a quarter of a million pounds, which if it had been successful, would have left them homeless and destitute as well as threatening the sequestration of the union’s assets.

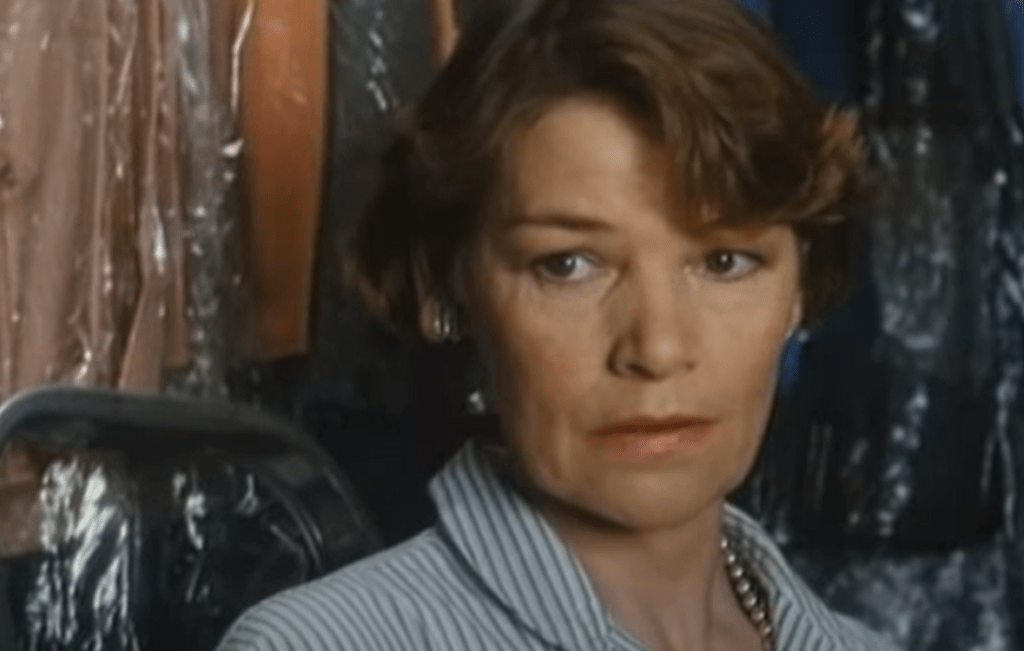

Audrey’s fight was so extraordinary, so brave and so stunning was her victory against such overwhelming odds, that a film was made in 1987, directed by Lezli-An Barrett, loosely based on her experiences. Business as Usual, starred Glenda Jackson and John Thaw, although Audrey herself would say that it is not the film that is important so much as winning that dispute.

If the dispute had been lost, how many tens of thousands of women workers would now have had to suffer in silence as they were sexually harassed at work? It is also no exaggeration to say that Audrey standing up against sexual harassment was in many ways a precursor to the “Me Too” movement.

Hard-pressed women workers

Today, after thirteen years of Tory austerity, the cuts to health and social services have placed ever more burdens on hard pressed women workers, to fill the gaps in the provision of care that those cuts have created, and with job security almost non-existent. The film demonstrates Audrey’s resistance and the contempt that capitalism shows to women workers. It was truly inspiring, a struggle that has given us an example from which we can learn vital lessons in our struggles today.

The dispute at Lady at Lord John did not drop from a clear blue sky. 1983 was a year of great social strife in Britain, as the Thatcher government, elected in 1979, led attack after attack on sections of the organised working class, reaching their highest expression the following year in the great miners’ strike. The city of Liverpool was also at the centre of many of those attacks, with large employers closing their doors and many bitter strikes taking place.

The city had been in economic decline since the late 1960s, with the local working class paying the price for the capitalists’ failure to invest and modernise. Unemployment levels were among the highest in the country, and job vacancies were scarce. In July 1981, typists employed by Liverpool City Council went on strike. During that six months’ strike, the 450 women workers struggled tirelessly to win their battle. The courage and commitment of these women workers, who had hardly been involved in union activity before, was an example to all.

School occupied and run by local community

At the time, it was the longest strike by white collar women workers in the UK. In early 1983, the Croxteth Comprehensive School was still being occupied and run by the local community with approximately 350 children attending at its height. There was a high level of class struggle taking place in Liverpool and women workers were playing a prominent role in those actions.

On April 23, 1983, the dispute at the Lady at Lord John store in Church Street, began completely unexpectedly. Audrey White had been the manager of the store for less than three months; she was a long-standing Labour Party activist and the sole member of the TGWU union in the shop, but she was no rabble-rousing troublemaker.

Lady at Lord John was the female clothing offshoot of a chain of originally men’s clothing shops, Lord John, which had begun in Carnaby Street, London, in the late 1960s, supplying high quality fashionable clothes at the top end of the market. By 1983 it had nationally nearly 300 menswear and over 200 ladies’ clothing outlets, becoming eventually Next stores.

The shop itself had just had a facelift, as the company was just beginning to invest into women’s clothing, confident of profitable returns. Thus the relaunch of the newly refurbished shop coincided with their dispute with their manager over the sexual harassment of their staff.

While the shop itself had received extensive remodelling, the same could not be said for the uniforms of the approximately a dozen female members of staff. Although they were given a choice of clothes supplied at discount by the company, which they were compelled to wear in the shop, they were of poor quality and the staff still had to pay for them out of their wages.

Poor quality clothing for staff

When the women highlighted the contradiction between a newly revamped shop being staffed by assistants in poor quality clothing on Saturday 23rd April the area manager offered to examine their uniforms. He then made unwelcome suggestions to a number of the young women, pulled one woman’s bra strap down, lifted up skirts of others and made personal comments.

It was then that four members of staff felt that the area manager had so physically overstepped the line that they complained to their shop manager, Audrey White. She in turn complained to the area manager, telling him not to behave like this and not to treat the staff that way.

The following Monday area management phoned Audrey and told her she was sacked, refusing to give any reason. When Audrey carried on working as she had been given no written notice or reason for dismissal, the management then called the police and she was removed from the premises by the police. Audrey had only been at the boutique for three months, and therefore could not take the firm to an industrial tribunal. Instead, she took the only effective course open to her: she called in her union, the TGWU.

On the following Saturday, men and women trade unionists picketed the shop. Placards explained the situation, although sexual harassment was at that time much more widespread, some male managers seeing it almost as a perk of their job. The term “sexual harassment” was not well known, as so little had been done to eradicate this misogynistic practice. It wasn’t easy for the pickets to find a form of words that would convey what the staff were being subjected to.

On the initiative of outraged passers-by, a petition calling for Audrey’s reinstatement was started, with three thousand signatures collected on the day. People queued up to sign. The picket was so successful that, it is estimated, the shop was losing nearly £6,000 worth of business a week.

Police arrested several pickets

On the following Monday, the union was invited to a meeting with management and an offer of money to Audrey to end the dispute was made, which she refused. The pickets continued. At one point, some three weeks into the dispute, one Saturday afternoon the police arrived with a police van and the pickets were ordered out of Church Street.

The police arrested everyone on the picket line, seven men and a young schoolgirl were shoved into the police van They were taken to the police station, held for five hours, and charged with obstruction The pickets were all imprisoned until around 10 o’clock that night. The pickets had all been shoved into a police cell and the young school girl who was only around 16 years old, was strip searched in a cell with the cell door open. It was only after MPs, Eddie Loyden, Bob Parry and Eric Heffer, attended the police station that they were released.

None of the male pickets got similar treatment, and given the nature of the dispute this could only be seen as a provocation by the police: a young woman protesting against sexual harassment being forcibly sexually harassed herself. Not surprisingly, an official complaint was then taken out by the parents of the young girl. She eventually won her complaint against the police and she was advised that the police responsible would be disciplined. Not unexpectedly, it was later heard that one of them had actually been promoted.

The picket began to attract support from local Labour councillors as well as the three the local Labour MPs, Eddie Loyden, Bob Parry and prospective parliamentary candidates. It received wide publicity in the local papers and on regional TV and radio. Daily picketing, which obviously included Audrey White’s family and people from organisations as diverse as the Kirkby Unemployment Centre and local MPs, was effectively a challenge to the law on secondary picketing brought in by the Tory Employment act 1982.

Thousands more names were collected on petitions and very few customers crossed the picket line. The TGWU picket was made up of predominantly male members from the local docks and car works, as well as unemployed members from the unemployment centres, which shows the real value of unions maintaining the unemployed in trade union membership and involving them in the activities of the union.

“no-one crosses a picket line in Liverpool”

“We picketed six days a week, all day, getting thousands of people to sign our petitions and boycott the shop,” Audrey said. And it was successful, because, as she added, “nobody crosses a picket line in Liverpool.” The response of the public was overwhelmingly sympathetic.

There is no doubt that the vast majority of working people in Liverpool felt that it is about time the bosses understood that women workers would not tolerate sexual harassment. Many shop workers and office workers explained, when signing the petition outside the shop, that they too had experienced sexual harassment at work. Support from the general public was so great that 15,000 signatures were eventually collected calling for Audrey’s reinstatement.

The company which owned the shop chain then tried to cut their losses by offering Audrey two alternative jobs in their other stores, one in a small shop in Liverpool, and another in a shop in Warrington. She had no hesitation in refusing these: they represented a wage cut of £50 a week and demotion.

If she had accepted, it would have implied fault on her part, so nothing short of reinstatement would have ended the dispute at this point. The employers were clearly on the back foot and reeling from the effects of the solidarity shown and the support Audrey was receiving from the union and the public.

Punitive damages sought for “molestation” of company

Eventually the company was forced to concede when their attempt to get an injunction against Audrey, her family and the TGWU for £250,000 of punitive damages failed, ironically itself claiming “molestation”. This was at the High Court in London, although the injunction wasn’t defeated so much by the High Court as by solidarity action.

The pickets had signed to say that they would picket ‘legally’ but as soon as they returned, they were back on the picket line and spread the action across the country. So, in effect, they were picketing illegally. In other words, they broke the law, and actually won the dispute because they stepped up the picketing at the Lady at Lord John stores in Manchester and London. Before then, the dispute was a stalemate.

Despite using the police, the state, the law and the courts in the most vicious and unscrupulous way, the company was unable to force one woman worker to submit, because she had on her side the support and solidarity of the trade union movement. The eventual outcome was talks between senior management and the TGWU and Audrey was fully reinstated without loss of pay.

The union made no concessions to management whatsoever and secured a total victory. It was won by the determined efforts of TGWU 612 branch, and the Liverpool labour movement, despite management’s attempts to intimidate the pickets into submission. The victory represented a great step forward for all shop workers, for whom sexual harassment is just one aspect of bad working conditions, and showed the value of joining and being active in a trade union.

Audrey White reinstate

Audrey White was reinstated as manager. But alongside her, there was still the same area manager, whose conduct had provoked the strike, as well as the shop manager who was in place during the dispute.

When Audrey returned to work she was still unable to take her complaint to a tribunal, because she hadn’t been there long enough. However, with the assistance of the Equal Opportunities Commission and the union she was again able to threaten to claim constructive dismissal because of the harassment she was now subject to.

Eventually, an agreement was arrived at, which involved the removal of the area manager and two others. Moreover, around the same time, all charges against the seven arrested pickets were dismissed in court and for the first time in history the union’s costs were awarded against the police.

Audrey fought forty years ago and won, and her fight led to a significant improvement in the working conditions faced by women. She is still fighting to this day and addressing other women workers. She would urge them to join that fight, even if at this moment in time they feel you can only take the smallest, most modest step.

“Join a union! Get active! If we don’t fight, we cannot win!”

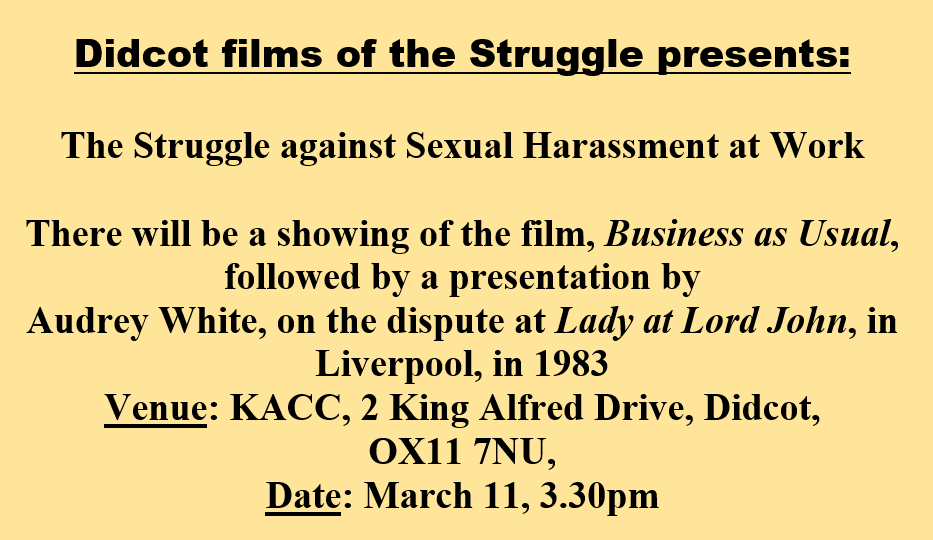

There is a screening of the film Business As Usual, organised by ‘Didcot films of the Struggle’ on Saturday March 11, at 3.30, followed by a discussion. See inset (above) for details.

For anyone unable to get to the Didcot meeting in person, you can see the film on YouTube here and you can participate by Zoom in the discussion following the presentation by Audrey White at 6pm, using this Zoom link (Meeting ID 853 8225 8967, passcode 277911).