By Mark Langabeer, Hastings and Rye Labour member

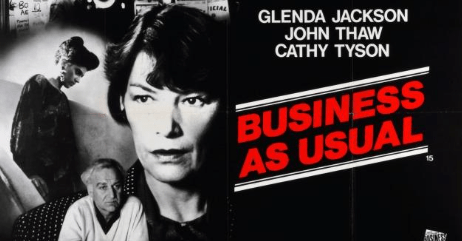

Business as Usual was a ‘low budget’ film, made in 1987, but was based on real events that took place in Liverpool in 1983. Its stars include Glenda Jackson, who became a Labour MP in 1992, after a distinguished acting career, and John Thaw, also regarded as one of Britain’s finest actors.

Why, then, review a film based on events from forty years ago? Simply because the problems facing society, and women in particular, at that time remain as relevant as ever today. The film is an inspiration to any women facing sexual harassment or discrimination at work today, and it is important in the context of the fight to end all violence against women and girls.

The story of the film is about a family rooted in the Liverpool Labour movement. The husband, played by John Thaw, was a former trade union convener at Tate and Lyle, but the factory had closed – as indeed it had in real life – and he had been unemployed for three years. He regarded himself as what was described in those days as a house husband. Both his son and daughter-in-law were active in the Labour Party.

Son was a supporter of Militant

The daughter drove a Robin Reliant with a big Vote Labour sticker on the back window. The son is shown in the film as a supporter of the paper Militant, selling outside a factory gate, another real-life scenario. It is only the mother of the family, played by Glenda Jackson, who is not active, although that all changes in the film. Although the film uses a lot of poetic license in the making, it is loosely based on the dispute led by Audrey White at Lady at Lord John (see article here).

In the film, Jackson works as a manager in a high street boutique and when a sales assistant complained to her about the attentions of the area manager, a serial groper, Jackson asked him to stop the harassment and she was promptly dismissed. It was her husband who then suggested that she should report to work as usual and request a written letter with reasons for dismissal. Her son also suggested joining and contacting the local organiser of the TGWU union, now Unite.

When Jackson followed her husband’s suggestion, she was promptly escorted off the premises by a police officer. She joined the T&G, who attempted to arrange a meeting with the boutique’s managing director. The company refused to meet the union, so an official from the unemployed members’ section, with other supporters, decided to launch a petition and a picket outside the shop. It proved so effective that the boutique had no customers for the entire duration of the campaign for Jackson’s reinstatement.

The company eventually agreed to meet and offered a month’s notice money. This was refused. The campaigners, who now included the local Labour Party Young Socialists, decided to extend picketing to other stores owned by the same company and at last the management caved in and reinstated Jackson as the boutique’s local manager.

The film had a number of sub-plots. The role of the police force, for example, who arrested and charged eight activists. The charges were later dismissed by a judge because of the inconsistencies in the evidence given by police officers. Then there was the district union official, who was often in disagreement with the branch officers over the best tactics to use. He feared that extending the picket to other stores could be deemed as ‘secondary action’ – which was then (in theory) illegal – and he thought it may have led to union funds being sequestrated. But when the district official said that talks could only commence “if the picketing was called off”, the local union officials refused and that proved to be the right decision.

Local and district union officials often at loggerheads

Supporters of Militant were very influential in the Liverpool labour movement at that time, including among members of the local unemployed T&G branch. Their approach to this and other campaigners was in sharp contrast to the half-hearted attitude often given by union district officials. At one point, Jackson gives an address to what appears to be a meeting of the Liverpool District Labour Party. Having never been active in the labour movement before, the events of the strike and the experience of solidarity from the labour movement, completely changed her view. In my view, that was the most important message of the film.

No doubt the film will have its critics. It has a Hollywood-style finish, whereby justice always prevails, but real life is never so simply and victories are often hard-fought. Events such as these often tended to go below the radar at the time. The attitude of the bulk of the press at that time often to trivialise sexual harassment and such behaviour was even ‘normalised’. I recall male workers hooting and catcalling whenever a young women came onto the factory floor.

But it was the real-life struggle shown in this film, as well as others like it, that made sexual harassment at work a serious issue. It paved the way for redress at industrial tribunals and anti-discrimination laws. Business as Usual is a film that should be watched by labour movement activists and it is still available on YouTube.

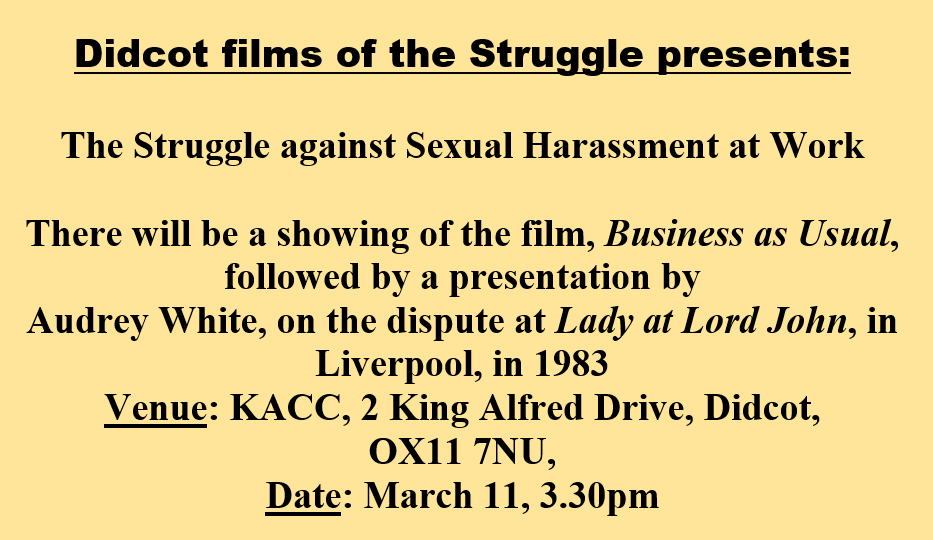

There is a screening of the film Business As Usual, organised by ‘Didcot films of the Struggle’ on Saturday March 11, at 3.30, followed by a discussion. See inset (above) for details.

For anyone unable to get to the Didcot meeting in person, you can see the film on YouTube here and then participate by Zoom in the discussion, following the presentation by Audrey White at 6pm, using this link (Meeting ID: 853 8225 8967, passcode: 277911).