Throughout this 40-year anniversary of the miners’ strike, Left Horizons will publish regular updates on how the strike developed around the country, as it happened, during the year-long dispute, as well as specific articles analysing major features and significant events.

**********

Coalfields in ferment

The National Coal Board (NCB), a nationalised industry, announced in early March the closure of 20 pits, with the loss of 20,000 jobs. This would have been in addition to the unprecedented 20,000 jobs already lost in the year before the strike!

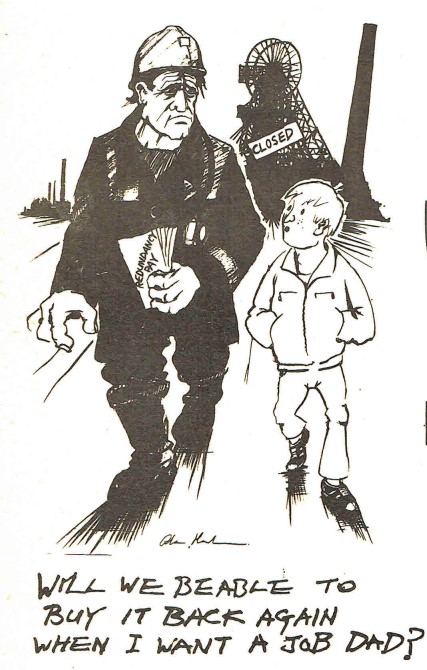

Many miners and the NUM leadership were certain that even these closures and job cuts were just the beginning of a Tory plan to destroy the industry, with up to 70 pits secretly earmarked for closure, including some of the most “efficient” pits, in the Midlands, that thought they were safe. This was borne out by government documents released decades later. The attack on the mining industry was one of many savage blows by the Tories against the organised working class.

The miners of Cortonwood, in Yorkshire, went on strike against the closure of the pit and called for solidarity action. Back in 1981 a ballot was held to support strike action in the event of pit closures. Yorkshire area voted in favour by 80 percent. The NUM leaders and miners in the threatened pits relied upon this to call for solidarity from the rest of the industry. 56,000 Yorkshire miners went of strike, and called on others to do the same. They pointed out that Yorkshire pits were not even the bulk of those most under threat, but that a stand had to be taken.

The first few weeks of the strike saw determined, sometimes frantic, efforts to maximise the support within the separate areas of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) for wider, national strike action. Different pits and areas varied in their levels of support. Some pits in Yorkshire were already taking action over the issue of breaks and safety issues – in reality these were attempts by the NCB to weaken the overtime ban that had been in place for 19 weeks, and boost production before they (in reality the Thatcher Government) provoked the strike.

Patiently explain

Many miners, particularly those who were older, were naturally tempted by the offers of “generous” redundancy payments, and the more active and militant miners needed to patiently explain the issues and the importance of not, in effect, selling future jobs. A whole layer of new, younger miners played an active part in resisting redundancies. They knew that their communities would have no future if the mines closed. Pits should only close when the coals stocks were exhausted – and even then, new jobs needed to be created to replace those lost.

In South Wales, in St John’s colliery, only 5 out of 400 voted not to strike, while at Tower colliery it was unanimous – a testament to bold and clear leadership. Some other pits in South Wales, however, initially voted 2:1 against. They had to be persuaded to forgive and forget the lack of solidarity with their own earlier strike, and not to take redundancy payments. 10 pits came out immediately, and within a couple of weeks, the last two working pits had joined them.

Ian Isaac, lodge secretary at St John’s, said that miners should “draw on the traditions of solidarity and comradeship and unite as never before.” He said “For many pits and for entire coalfields, the issue is literally survival or annihilation”. Stan Pierce, from Monkwearmouth colliery, in Co Durham, predicted that miners would “vote with their feet” in solidarity. (Militant 9 & 16 March 1984). At Boldon colliery, in Durham, one picket, Norman Strike (yes – his real name!) turned away six lorries on his own. At a 600-strong lobby of NUM headquarters, the mood was jubilant.

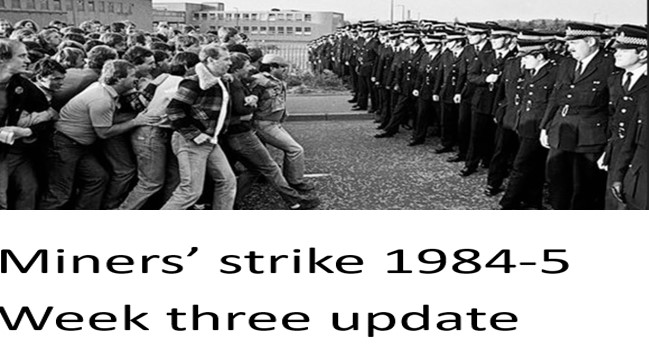

Picketing successes and fatal divisions

Pit after pit, up and down the country, from Scotland to Kent, did join the strike but tragically, not all areas came out, particularly in Nottinghamshire and other Midland areas and Lancashire. These areas had the easier coal seams and were more productive. They had enjoyed higher bonuses since the area bonus scheme had been introduced in 1977 and they thought their jobs were safe. Even here, though, pickets from other areas, together with local striking miners did score early successes. Yorkshire miners went to Bevercote in Notts, and reported that 90 percent did not cross the picket line. At Bolsover, in Derbyshire, nobody crossed a picket line.

The key was to have the opportunity for pickets to have a proper meeting with miners and persuade them to come out. This is what happened at Lea Hall colliery in Staffordshire. Many miners in areas with weak or vacillating local officials were not fully informed of the issues at stake. In Nottinghamshire a ballot was held at a pit heads, without a chance for the pickets to explain the issues properly. Miners were voting in isolation and the result was negative.

75 percent of miners had, indeed, voted with their feet, and 134 pits were closed, but the 25 percent who continued working seriously weakened the miners’ ability to win. It was even suggested by some that the striking miners in Notts should be given dispensation to cross picket lines in order to go in to the mine and persuade their workmates to join the strike.

However, by then, 8,000 extra police, from sixteen other county forces, had been drafted into Notts and Derbyshire with the express intention of preventing pickets from persuading working miners – scabs – to join the strike. Nottinghamshire was virtually sealed off. Miners from Yorkshire were even prevented from driving across the border to visit friends and family! Of course, many Notts miners did go on strike, and deserve enormous praise for their courage and determination, but they had to live amongst sometimes hostile divided communities.

Death of David Jones

It was in this increasingly bitter and confrontational atmosphere that a 24-year-old miner from Ackton Hall pit in Yorkshire, lost his life. Picketing miners in Ollerton in Nottinghamshire, had been held behind police lines while people turning out of a pub were abusing them and causing trouble. David got away to check on his car, which was parked in the village, and got hit by a brick [nobody was ever charged with his killing].

killed at Ollerton in March 1984

In the early morning on 15 March at Ollerton colliery, pickets held a two-minute silence, even demanding that the local police took off their helmets in respect. His funeral was held on 23 March and thousands of miners and their families and other socialists and trade unionists, with their banners, attended to show their respects.

Triple Alliance

Even at this early stage, many of the most active striking miners and their supporters were raising the demand for a Triple Alliance of miners, steel workers and rail workers as the key to winning the dispute. The steel workers and their union, the Iron and Steel Trades Confederation (ISTC), had been attacked by Ian McGregor while he was boss at publicly-owned British Steel, leading to the closure of steel mills and the loss of thousands of jobs. The same McGregor, now boss of the NCB was using a fall in demand for coal in steel plants to justify pit closures. How long would it be, it was argued, before the reduction in the use of coal would lead to job losses on the railways?

Community support

As soon as the strike got going there was an upsurge in support in the general public. People were phoning up to offer use of their cars to carry people to picket lines and other meetings. In Mid-Glamorgan the local Labour County Council offered free school meals for the children of striking miners. Another local council in South Wales suspended rent payments during the strike! Some local petrol stations offered cheaper petrol to strikers! Sadly, not everyone was so supportive. There were reports of younger striking miners in private rented accommodation being evicted by their landlords.

Women in the mining communities

Thatcher and the Tories counted on the wives and partners of miners to be a source of weakness, providing pressure to go back to work. They had cut any payments of Social Security Benefits to strikers’ families to ratchet up the pressure. In this they drastically miscalculated. From the beginning, it was clear that miners’ wives were fully behind the fight to preserve jobs and save the communities.

One miner’s wife, Ann Kendrick from Westoe, in Co Durham was reported as saying:

“Obviously miners’ wives don’t like the men being on strike. But if we don’t stand and fight, we’ll have no jobs and no wages. As for the women shown on television escorting husbands through picket lines, I just wish the NUM would organise a bus for the wives who support the strike. We’d show them a thing or two. If any “pinny brigade” tries tricks like that here, I’d be on the picket with my husband pushing the other way.”

Militant – 23 March 1984

A letter from Kent to the leaders of the Nottinghamshire miners summed up the feelings very well.

“We are Kent miners’ wives, proud of our men in their struggle against pit closures, and we are sure we speak for many miners’ wives around the country.

“Recent events have proved difficult and distressing for all miners’ families involved in the dispute but the most distressing point of all is the ‘I’m all right Jack’ attitude of the majority of your members. This dispute is about pit closures, jobs and a future for all in the industries. It will affect your area as well as the rest of Britain […]

“We understand the pressures – we are living through it too. We struggled to survive in 1972 and 1974 strikes because we believed in what we were fighting for. We are willing to struggle again. This case can be won – it must be won.

“It is the most important battle of our lives – it is a fight for our future – the survival of Britain’s finest industries and a lot of mining communities. Our fight should be your fight. No miner has the right to take another man’s job in the future. Challenge your members to think again and unite behind the leadership in an effort to secure a future for all.

“Yours sincerely,

Mrs K N Sutcliffe

Aylesham Ladies Section,

Friends of Mineworkers,

Snowdown Colliery.”———————————————————–

Militant – 23 March 1984

*Look out for future updates as the anniversary of the strike continues over the coming year.*

[NB – Much of the information in this article comes from issues of the newspaper Militant on 9, 16 and 23 March 1984]