By Sam Gleaden, mental health worker

The ‘low serotonin’ hypothesis has been the backbone of the psychiatric approach to depression for the past 40 years. It claims that mental health issues are caused by a “chemical imbalance” of neurotransmitters, the brain’s chemical messengers.

But in July 2022, a controversial Umbrella analysis hit UK headlines, summarising decades of evidence; it showed conclusively that there was little scientific basis for the “low serotonin” theory of depression.

Yet surveys show that 80-90% of the population now believe that mental health issues are caused by these chemical imbalances and the spread of this idea has had huge sociological and political ramifications. Millions have been left believing they are genetically wired for suffering, while the overwhelming distress caused by modern capitalism is let off the hook.

Chemical imbalance and the medical model of mental illness

The chemical imbalance theory is linked closely to the medical model of mental illness, which states that there are specific biological mechanisms which cause discrete forms of psychological distress, akin to physical illnesses or diseases of the brain. The explanation for these ‘diseases’ mainly focuses on genetic differences, and the emphasis is on the biology and brains of individuals rather than their life histories or environments.

Although a number of studies have been made into other “biomarkers” (consistent biological evidence), the levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin, which is involved in mood, sleep and digestion, remain the most researched.

Yet six different measures, ranging from the number of serotonin receptors to evidence of serotonin in the bloodstream, have shown no clear link between the amount of serotonin and the likelihood of depression. What this research and the lack of evidence of other biomarkers for depression is making clear, is that the complexities of human suffering can’t be boiled down to quantities of a few basic neurochemicals.

This isn’t to say that our brains and biology are not important; in fact, they are involved in some way in all our experiences. However, our emotional well-being is dictated by a highly complex web of interactions, including our social environments, personal and cultural belief systems, the early ‘wiring’ of our nervous systems, genetic predispositions, and so on.

Promotion of chemical imbalance theory by Psychiatry and Big Pharma

So why has this incredibly oversimplified view been promoted in western culture for decades? This disease-based medical model of understanding depression has its roots in academic psychiatry from the 1960s.

In her book The Myth of the Chemical Cure, Joanna Moncrief outlines a shift in psychiatric attitudes to new medications being developed. Previously, medications used in mental health were seen in the same way that we might imagine sedatives working, by dampening our normal functioning to produce a temporarily useful altered state of consciousness.

Psychiatry, which throughout its history was keen to be seen as an empirical scientific profession much like medical doctors, started to present new medications differently. They were promoted as working on a specific underlying disease caused by a “chemical imbalance”, with psychiatrists as the guardians of the knowledge for these “diseases” of the mind.

Psychiatrists promoted this view in tandem with a growing pharmaceutical industry. With the discovery of new SSRIs (a group of anti-depressants) in the 1980s, big pharmaceutical companies went into overdrive to promote the disease-based “chemical imbalance” theory and the need for SSRIs.

Following deregulation, direct consumer advertising spending on drugs ballooned in the USA in the 1990s, going from $25 million in 1988, to over $1bn in 1996, with psychiatric medications being the largest share. Today, $5bn is spent on drug advertising alone.

With adverts like this, for Zoloft (called sertraline today), commercials were everywhere in the 1990s and early 2000s. In 1999, it was estimated that the average American saw nine adverts for drugs every day.

Pharmaceutical Industry control of psychiatry

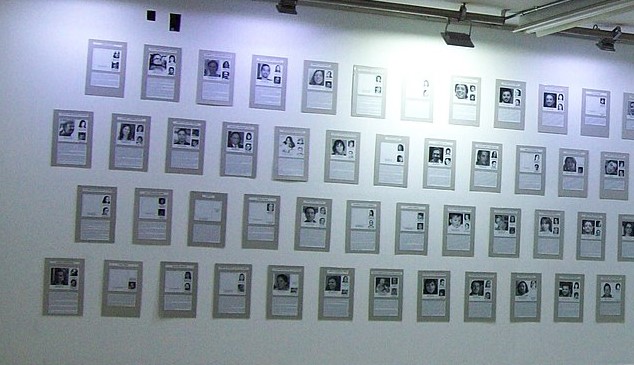

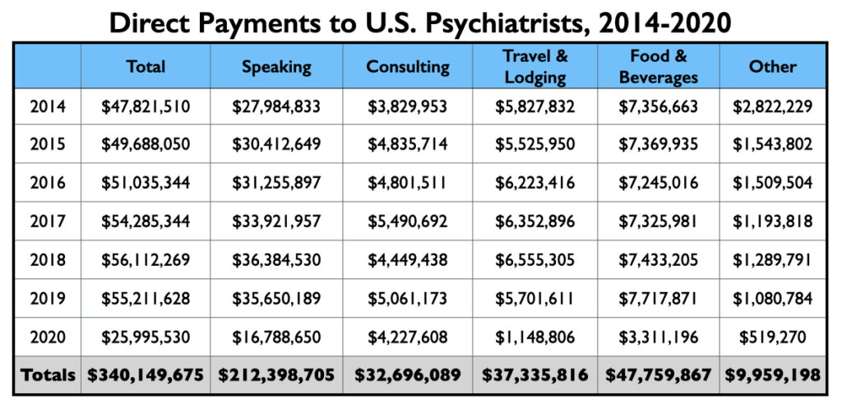

In most countries however, direct advertising of drugs like this is illegal. Generally, the pharmaceutical industry has influenced the population through its staggering financial domination over the psychiatric profession globally. Many leading psychiatrists, some with huge authority in the field, are funded by big pharma. Their influence is used to promote certain medications through professional talks and by promotion in academic journals. Half of the biggest donations from all pharmaceutical companies to medical professionals went to psychiatrists alone.

Educational conferences for psychiatrists are now dominated by Big Pharma. Psychiatrist, Edward Torrey, explained that at the 7th World Congress of Psychiatry in 2001, $10 mn was spent by pharmaceutical companies on extravagant extras such as an artificial garden and circus acts, as well as airfares for all attendees and direct sponsorship of half the delegates.

In the UK, author James Davies has uncovered that many top UK universities are paid millions each year for research funding. Equally disturbing, BMJ (formerly the British Medical Journal) research found that clinical commissioning groups, which allocate NHS funding, are also being given millions by pharmaceutical companies, much of it hidden. The consequence of this has been a huge influence of medical practice. GPs for example, would regularly prescribe psychiatric medications and give the “chemical Imbalance” explanation as justification.

A tenth of the population take mental health medication

One clear side effect of this culture has been an explosion of the use of SSRIs and other psychiatric medications. Around 10% of the UK population iscurrently taking some kind of psychiatric medication with similar rises found globally. Meanwhile, evidence is increasingly showing that the prolonged use of such psychiatric medications can actually be harmful to those who take them.

To be very clear, this is not to say that psychiatric medication is inherently bad or that taking it is wrong. But there has been a complete lack of transparency from pharmaceutical companies about their long-term side effects and overall effectiveness.

Many investigations have now revealed that much of the research around psychiatric medications is biased in favour of medications. Inquiries have found either unconscious bias or straight-up malpractice are commonplace in the profession. This is unsurprising, given that most of the research on medication is done by psychiatrists with direct financial ties to the pharmaceutical companies themselves.

The other more subtle cultural effect has been the ‘internalisation’ of the disease-based understanding of mental distress, as a set of biologically driven “illnesses” rooted in the brain.

Research shows that when psychological distress is framed in a biological and individualised way, blame on the person is lessened; however, stigma about their chances of recovery, desire to befriend them, and prejudices around their behaviour, such as increased aggression, all worsen.

The paradox of our current culture around mental health is that although we are more understanding of people receiving treatment, the way we understand “mental illness” can increase the stigma and division between those with “mental illness” and those without. Rather than seeing mental health as a spectrum along which we all move back and forth, depending on life circumstances and life histories, our current “disease-based” framework can be divisive.

I’ve seen the danger of this in mental health services, whereby people only feel their distress matters if they have a diagnosis and are deemed “unwell”. On the reverse side, some of those who might need support will hesitate to access it, out of fear of being labelled as someone with mental health issues. This culture of “othering” those who are mentally ill is a repercussion of the wider ideological framework that benefits big business and the capitalist class.

Historically, with the rise of capitalism and the subsequent need for a hard-working labour force, asylums were part of a network of institutions created to deal with those deemed unfit for the workforce. Our modern welfare state system echoes this culture by focusing on getting people “well” enough to work again, rather than having a holistic focus on well-being.

Huge profits for “Big Pharma”

Big business makes huge profits by commodifying our distress. Not just with the $22bn anti-depressant market, but the whole $275bn well-being industry selling us fitness programmes, self-help books, and mindfulness apps. Although these products can be useful, they often trap us into believing that solutions to distress lies with individuals rather than collective political movements of liberation.

On top of the profitability, the idea of “mental illness” itself promoted through the “chemical imbalance” theory takes society’s focus away from our failed economic system and government policies. There is now a growing phenomenon of the “psychiatrisation” even of social problems such as domestic violence, child abuse, school failure, unemployment and so on. An example of this is the rapid rise in the numbers of school children – in overcrowded classes and under extreme exam pressure – being given labels of ADHD and anxiety disorders needing ‘support’ with medication.

In all these examples, the ideology of “mental illness” focuses on blaming and shaming the individual for issues created by society, disguising the oppressive role of big business and its economic system.

A new way forward?

More holistic models of human suffering, which move away from the medical model of mental health, are becoming increasingly popular within healthcare. Trauma-informed care (TIC) and the more controversial Power Threat Meaning Framework (PTMF) look at the context of people’s lives, and in particular, the role of challenging or traumatic life experiences.

PTMF puts our suffering in its social context by examining how power operates in society, such as the way our economic system traps people in poverty, or the consistent gaslighting of women in a society rife with sexism. These models of understanding mental distress can be best summarised by moving away from asking “what’s wrong with you?” to “what’s happened to you?”.

Although these ideas are growing in popularity within the mental health profession, and through various activists on social media, they will come up against the vested interest of big business. The worker’s movement can, and should, act as a mouthpiece to promote frameworks like these.

These new ideas can both liberate us from the blame and stigma that capitalist ideology creates, while also pointing a direction forward through the transformation of society via collective political struggle, rather than as isolated “chemically imbalanced” individuals.